reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches

- This topic has 7,926 replies, 103 voices, and was last updated 8 years, 10 months ago by

Praxiteles.

- AuthorPosts

- October 21, 2005 at 10:30 am #708442

GregF

ParticipantI dunno if this has been discussed before on a different thread but I saw on the Irish Times this morning that Kevin Myers raises the issue of the proposed renovations of St Colmans Cathedral in Cobh. I had heard this before and couldn’t believe it. This is a fine Victorian Gothic cathedral designed by Pugin. Surely any tampering with the orignal features would be an act of vandalism and must not go ahead. As I said before, the councils, clergy etc… here in Ireland can’t seem to leave well alone regarding important public buildings, statues etc…..All Corkonians should be up in arms and stop any proposed tampering that should alter the cathedral in any way, especially as it was probably the poor local Cork Catholics that provided the funds to build the cathedral in the first place.

(Bishop McGee of Cloyne is the culprit. Get writing your protest letters rebel Corkonians!)

- October 21, 2005 at 12:42 pm #767215

Anonymous

InactiveApparently there were 210 objections and the list of Appelants included

Department of the Environment

Irish Georgian Society

An Taisce

Friends of St Colmans (largely made up of the parish council of St Colmans)

He was trying to get internal parish support for this for almost ten years and despite everyone elses opinion he is hell bent of leaving his what would appear extremely destructive mark on what is already an excellent interior.

- October 21, 2005 at 1:47 pm #767216

emf

ParticipantI wandered into St. Colman’s when I was in Cobh last year and I was very emotionally moved by the peace and tranquility there.

No doubt in some way it related to the scale and grandeur of the building itself. I’m not sure if this re-ordering is a good idea. It definitely shouldn’t be carried out on the whim of one person. I know I definitely wouldn’t be affected the same way going into one of the modern creations.It might be good to sound out opinion on the re-ordering of Carlow Cathedral a few years ago. I was in the church many times before it was carried out but moved away before it was completed.

- October 21, 2005 at 1:52 pm #767217

ctesiphon

ParticipantThere are special DEHLG guidelines for churches that are protected structures, such is the sensitivity of the area. Ultimately, liturgical requirements take precedence over conservation requirements. But interestingly, when Ratzinger was a Cardinal he wrote a piece (don’t know the chapter and verse, sorry) saying that there was no liturgical rationale to remove altar railings or other features, which is the reason usually cited by those trying to change things.

And didn’t Jesus himself say ‘wherever two or three are gathered in my name’ or words to that effect? Christianity began in caves and back rooms, so the setting is surely incidental to the practice. Why can’t the Bishop understand this?

Though not a believer, I have been to mass in the Cathedral on the basis that a building comes alive when serving its purpose, and it was a fine sight indeed. - October 21, 2005 at 2:15 pm #767218

Paul Clerkin

KeymasterThey did something similar at Monaghan and ruined it. And the bishop is still a little sensitive about criticism.5 or 6 years back I said something negative here, and the next thing I get a letter from a dioscesan flunkey asked me to desist.

- October 21, 2005 at 3:16 pm #767219

lexington

ParticipantYou’d think of all people who should value the integrity and splendour of such a magnificant structure, it would be the Bishop of Cloyne and Cobh, but no. I’m very much supportive of the opposition on this front – the proposed changes are not necessary requirements. It’s a very diappointing scenario. In Ireland, and certainly in Cork, it is perhaps on of the most tranquil and architecturally inspiring structures of a religious nature – especially inside. Along with St. Peter’s & Paul’s near Paul Street and St. Fin Barre’s – it is among my favourite interior designs.

- October 21, 2005 at 5:54 pm #767220

GrahamH

ParticipantFrom the vague plans I’ve seen, the expansive altar interventions look like the flooring scheme of an 80s television chatshow – is it intended to cap it off with a salmon pink carpet?

While it is easy to view the structure as a purely architectural entity, at the end of the day it is a working religious building and as such its use is as equally important as its fabric. Saying that, surely the proposed alterations are not necessary, or at least not on that scale?

Whereas previous Vatican reforms were logical in altering the clearly skewed relationship between the celebrant and the congregation, the notion of ‘bringing the people closer’ in Cobh Cathedral – which by definition is going to have people somewhere in the building detached from the proceedings – seems to be founded in a vague symbolisim rather than practical concerns.

It would be a great shame to see the interior so radically altered – especially having survived so long as it has intact.

You’d think we’d be able to issue a sigh of relief by now having got through the 70s – clearly not. - October 21, 2005 at 7:04 pm #767221

ctesiphon

Participant@Graham Hickey wrote:

From the vague plans I’ve seen, the expansive altar interventions look like the flooring scheme of an 80s television chatshow – is it intended to cap it off with a salmon pink carpet?

With Anna and Blathnaid from The Afternoon Show giving out communion? Or Thelma and Derek?

Good point about the difference between this and the post-Vatican II changes too.

- October 21, 2005 at 11:37 pm #767222

PTB

ParticipantAs a member of the dioses of cloyne I must say that most people are fairly tired of sending off parish funds to fund the restoration. The work that was done from 1992 until 2002/2003 were the first four of five phases of restoration. This last phase is not so much restoration as an alteration. As well as the other objectors mentioned by Thomond Park are the Pugin society in London who are very angry at the proposed work, which is considered by some as Pugins finest work.

- October 23, 2005 at 2:52 am #767223

Anonymous

Inactive@PTB wrote:

This last phase is not so much restoration as an alteration.

That is an extremely mild description

- October 24, 2005 at 11:21 pm #767224

anto

Participantdidn’t eamonn casey “ruin” the cathedral in Killarney in a similar drive?

- October 25, 2005 at 12:42 am #767225

J. Seerski

ParticipantI think the problem is ideological – there is a body of opinion in the church that says that a church is not a museum but a living building that should be changed as they please according to their liturgical requirements. Though Im puzzeled as to why churches on mainland Europe and even in Britain retain pre-vatican two layout without much difficulty. It seems over here the churches are gutted just to prove a point.

Was in Iona Church (St Columba’s – a fine celtic revival church) on Sunday and I was amazed how it retained its pulpit and much of its altar railing was untouched. It seems this place was luckily overlooked when churches elsewhere were gutted.

- October 25, 2005 at 5:26 am #767226

Anonymous

InactiveThose are good points you make;

In essence the choice is not whether one wrecks masterpieces such as St Colmans but rather what one does with newly built places of worship. Surely if the parishioners of Cobh want a post V2 church atmosphere they can select another RC church on Great Island.

- October 26, 2005 at 8:09 pm #767227

Praxiteles

ParticipantThe text of Cardinal Ratzinger’s letter to Bishop Ryan of Kildare and Leighlin (12 June 1996) was published in the Carlow Nationalist on 10 January 1997 – having been requisitioned by the High Court. The full text is available on the internet at; htpp://www.ad2000.com.au/articles/1998/cot1998p10_544.html. The tragedy is that what has happend in churches throughout Ireland was liturgically needless.

An interesting summary on liturgical requirement is available on the news section of the webpage of the Friends of St. Colman’s Cathedral (http://www.foscc.com) prepared for An Bord Pleanala by Arthur Cox.

As is clear from the case of Cobh Cathedral, Diocesan Historic Church Committees are a complete farce. In this case, the Historic Church Committe of the diocese of Cloyne, mostly made up of unqualified persons, did not even bother to conduct a heritage impact study of the proposed changes on the interior of the building.

- October 26, 2005 at 11:26 pm #767228

ctesiphon

ParticipantThanks for that info Praxiteles (great name, btw!). The FOSCC site is a goldmine.

One minor correction, though, to the URL you posted.

http://www.ad2000.com.au/articles/1998/oct1998p10_544.html

This should work. 🙂 - October 26, 2005 at 11:32 pm #767229

GrahamH

ParticipantWhat came of the appeal to the Supreme Court do you know Praxiteles?

- October 26, 2005 at 11:35 pm #767230

Praxiteles

ParticipantAs far as I can make out from the webpage (http://www.foscc.com) the matter is still pending with An Bord Pleanala.

- October 27, 2005 at 12:05 am #767231

GrahamH

ParticipantSorry, I mean Carlow Cathedral – do you know what the Supreme Court ruling was from what seems to be 1998?

- October 27, 2005 at 12:28 am #767232

Praxiteles

ParticipantI do not, I am afraid.

- October 27, 2005 at 2:38 pm #767233

Gianlorenzo

ParticipantHow can the great Prof O’Neill have gotten himself involved in such a foolish enterprise

View his plans on http://www.foscc.com - October 27, 2005 at 2:39 pm #767234

Praxiteles

ParticipantThat is indeed a million dollar question.

- October 27, 2005 at 8:40 pm #767235

MacLeinin

ParticipantYou would think that after his disastrous fiddling with the pro-cathedral, he would have learnt his lesson.

I am told one local wag in Cobh referred to his current plans for the interior as an ‘ice rinque’ - October 27, 2005 at 8:53 pm #767236

Gianlorenzo

ParticipantThe Friends of St. Colman’s Cathedral are made up of a group of concerned Cobh parishioners, none of whom are on the parish council. To clarify information posted by Thomond Park

- October 28, 2005 at 9:05 pm #767237

Praxiteles

ParticipantDoes anyone have any biographical or professional information re Thomas Aloysius Coleman (1865-1952), who was George Ashlin’s partner while working on the completion of St. Colman’s Cathedral?

- October 29, 2005 at 12:16 am #767238

ctesiphon

ParticipantA former colleague of mine wrote a History of Art thesis in Trinity in 1999 or so, either M.Litt or M.Phil, on Ashlin. I’m sure it would have some info you require. I’ll send you her email by private message.

Also, the office of Ashlin and Coleman still exists, though without family connections to Ashlin or Coleman, I believe. They might be able to help re old drawings, company archives etc. A quick google gives two addresses: 36 Pembroke Road, D.4, or 1 Grant’s Row, off Lwr Mount St, D.2, and an email (possibly out of date) of info@ashlincoleman.com - October 31, 2005 at 1:48 pm #767239

MacLeinin

ParticipantIs that it? Is the whole of Ireland ‘comfortably numb’ ? Does writing here constitute action? Do we just let the Bishop and O’Neill get away with this? We can’t blame the politicians for this one. You all seem to know what you are talking about so tell me what can one do about this sort of thing?

- November 5, 2005 at 2:12 pm #767240

descamps

ParticipantI was in Cork last week and went out to see the cathedral in Cobh. It is truly spectacular and it is a small miracle that it has survived for so long without the kind of ravages practiced on Killarney by Eamonn Casey or on Monaghan by Joe Duffy. Looking over the plans for this fine little gem, I cannot help but think that John Magee and Tom Cavanagh (aka Mr. Tidy towns of Ireland) have more money than sense – or good taste.

- November 7, 2005 at 4:53 pm #767241

Praxiteles

ParticipantPerhaps the comments on architectural theory contained in the following link could be brought to bear on the Cobh Cathedral business: http://www.profil.at/?/articles/0544/560/125321.shtml

- November 7, 2005 at 6:32 pm #767242

Praxiteles

ParticipantFurther interesting comments are available on the subject of liturgy and architecture at http://www.kreuz.net/article.2121.html . Unfortunately, the English and French translations are very inadequate.

- November 7, 2005 at 7:46 pm #767243

Peter Parler

ParticipantHas Bishop Magee no fear of God? Could they not get Pope Benedict to scribble him a quick note to let him know they’ll soon be putting everything back the way it was before the liturgical vandals were let loose?

- November 8, 2005 at 1:02 am #767244

Gianlorenzo

Participant“When men have come to the edge of a precipice, it is the lover of life who has the spirit to leap backwards, and only the pessimist who continues to believe in progress.”

“It is of the new things that men tire – of fashions and proposals and improvements and change. It is the old things that startle and intoxicate. It is the old things that are young.”

Do pessimists fear God?

- November 9, 2005 at 6:54 pm #767245

Peter Parler

ParticipantThe article referred to by Praxiteles in #28 is absolutely relevant to poor Cobh. The Lady Church in Dresden was destoyed free of charge in 1945 and in its ruined state remained a monument to the barbarity of war and the atheistic convictions of Communism until its resurrection began in 1990, a symbol of generosity, reconciliation and a new freedom. Surely at this time of episcopal shame the Bishop of Cloyne could offer a similar generosity, reconciliation and renewal of freedom to the Friends of Saint Colman’s and all who care for our religious and architectural heritage, at minimal pain to himself or the coffers of his Diocese. Isn’t there something in the Gospel against Christians forcing one another to appeal to civil tribunals for justice? Isn’t pride a terrible, terrible thing? Haven’t we all better things to be doing?

- November 9, 2005 at 11:11 pm #767246

Praxiteles

ParticipantSomeone has pointed out to me that in 1999, the Cobh Cathedral restoration Committee received a grant of some £8,937 from the Heritage Council to finance a conservation study of St. Colman’s Cathedral.

The Conservation study was completed in early 2001 by Carrig of Dublin. This fine and original study was very competently carried out by Jesse Castle Metlitski and Richard Oram.

Along with synthesizing a vast amount of archival material, much of which was examined for the first time, the study produced an important photographic archive of Cobh Cathedral.

The authors of the study concluded: “The wealth of information and sources pertaining to the design and construction of St. Colman’s can provide a unique insight into the whole process of the construction of such a building as this cathedral while providing a remarkable record. The importance of this material can not be overstated. This, together with the definitive record which is the cathedral itself, must be preserved and safeguarded for future generations”.

The authors also note: “The design is very finely tuned and any interventions which might contradict the delicate interplay of parts have the potential to compromise the architectural quality of the building. When St Colman’s was build it was already one of the finst expressions of the Gothic Revival style in Ireland. This eminence has been held to the present day”.

The proposals for the reordering of the Cathedral’s interior pay not the slightest heed to such remarks and have been elaborated as though the Metlitski/Oram conservation report never happened.

- November 9, 2005 at 11:31 pm #767247

johannas

ParticipantDoes anyone have any information about Ludwig Oppenheimer’s career?

- November 11, 2005 at 12:11 am #767248

MacLeinin

ParticipantInformation on Ludwig Oppenheimer is difficult to come by. What I know is that, in addition to St. Colman’s Cathedral, he is credited with the magnificent mosaics in the National Museum of Ireland –Archaeology and History. The floors are decorated with scenes from classical mythology and allegory, and are worth a visit to the museum in themselves. He is also credited with the wonderful mosaic floor of the Honan Chapel, University College, Cork. Biographical details for Oppenheimer, I have found, is very difficult to come by, perhaps other visitor this site may be able to help.

- November 11, 2005 at 12:40 am #767249

ctesiphon

ParticipantThere was a lavishly illustrated monograph published not so long ago on the Honan Chapel (maybe by Cork University Press?). It might have some leads.

- November 11, 2005 at 1:03 am #767250

Praxiteles

ParticipantThis must have been Virginia Teehan and Elizabeth Wincott-Heckett’s The Honan Chapel: A Golden Vision published by Cork University Press in 2004. Chapter 5 of same, by Jane Hawkes, has a long excursus on the symbolism of the magnificent mosaic floor which is by Ludwig Oppenheimer. He is also responsible for the stations of the cross in opus sectile. Oppenheimer’s work in the Honan Chapel was never publicized for it was the only work carried out there by a non Irish company. It has been suggested that he was commissioned to execute the mosaic floor and the stations of the cross through the influence of the Cork architect Thomas Newhenam Deane or of W. A. Scott who had worked on the Dublin Museum. As in Cobh Cathedral, Oppenheimer’s mosaic work was complemented in the Honan Chapel by the brass and iron work of J&G McGloughlin of Dublin.

- November 11, 2005 at 3:39 am #767251

MacLeinin

ParticipantInformation on Ludwig Oppenheimer is difficult to come by. What I know is that, in addition to St. Colman’s Cathedral, he is credited with the magnificent mosaics in the National Museum of Ireland –Archaeology and History. The floors are decorated with scenes from classical mythology and allegory, and are worth a visit to the museum in themselves. He is also credited with the wonderful mosaic floor of the Honan Chapel, University College, Cork.

Biographical details for Oppenheimer, is very difficult to come by, perhaps other visitor this site may be able to help. - November 12, 2005 at 2:48 am #767252

Praxiteles

ParticipantLudwig Oppenheimer may well be responsible for the very elaborate moasic work on the floor and walls of the chancel of the church of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross in Charleville, Co. Cork. This work is about a decade later than Cobh Cathedral (Walter Doolin exhibited designs for the church at RHA in 1898) but the similarities are unmistakable (e.g. the floors of the Sacred Heart and Lady Chapels in Cobh and Charleville). Unfortunately, the floor in the main chancel space in Charleville has been buried under several tons of concrete to make an emplacment for a hidiously unsympathetic re-ordering. It is possible that Oppenheimer’ may have had the commission in Charleville through the patronage of Bishop Robert Browne who was a native of Charleville and, in contrast with the present encumbent in Cobh, a very generous benefactor both of St. Colman’s Cathedral, Cobh ,and of the new parish church in Charleville.

- November 12, 2005 at 3:24 am #767253

GrahamH

ParticipantAnother case of mosaics being covered over is in a modest but significant Ralph Byrne church c1920 in the North East, where the usual finance commitee of the parish elite saw fit to cover over the highly attractive grape vine mosaics of the altar floor with ‘a nice bit of carpet’ in the late 90s.

A large timber step was also partially built on top to regularise the step line and was also covered in carpet, which not only completely altered the nature of the altar design, but no doubt damaged the mosaics beneath too by its attachment to them, as with the carpet grippers drilled or glued onto the marble edging.

You see this type of practice a lot in small to middle-sized churches which is a great shame. - November 12, 2005 at 3:51 am #767254

Neo Goth

ParticipantI guess most people on this thread have visited the brilliant website by the Friends of St Colman’s Cathedral at http://www.foscc.com my compliments to the friends for trying to stop this latest outbreak of architectural vandalism.

Neo-Goths of the world unite and strike back!

- November 12, 2005 at 8:55 am #767255

Praxiteles

ParticipantIn Cobh Cathedral, for years the great central motif of the moasic in the chancel was covered by a green carpet ivo-stuck to the floor. In the first phase of the Cathedral restoration it was removed. Because it had been glued to the floor, and at a time when there was still some bit of respect for Oppenheimer’s work, it was taken up by steeping it in large quantities of petrol to avoid tearing up the tesserae of the mosaic. At that time, a phoney appreciation of the central chancel mosaic was used to justify removing the altar rails – all quietly forgotten, however, since Cathal O’Neill proposed digging out the entire floor, mosaic and all.

- November 12, 2005 at 12:41 pm #767256

Gianlorenzo

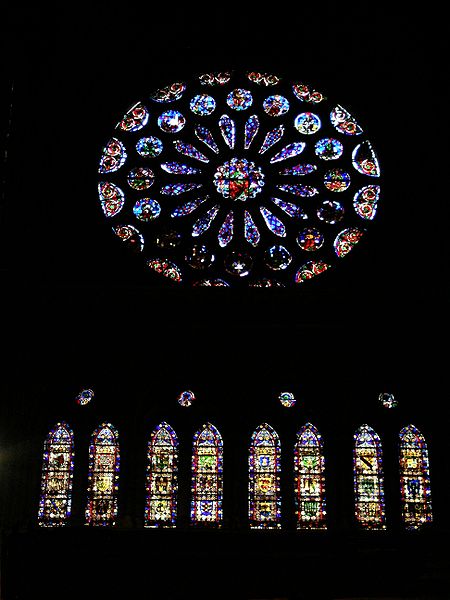

ParticipantOppenheimer is also credited with the design of the Clonard Redemptorist Church, Falls Rd., Belfast.

This church, also known as the Church of the Holy Redeemer, occupies a dramatic site on one wing of a three-sided courtyard. It is linked by a tower to the red brick and sandstone monastery extension. There is a large rose window in the west façade.

Clonard was designed in early French Gothic style by Ludwig Oppenheimer and built in 1897 by the Naughton brothers of Randalstown. It is home to the Redemptorists, who were founded in Italy in 1732 and contains mosaics from Gabriel Loire of Chartres. The Monastery was the scene of the first contacts that started the Northern Ireland peace process in the early 1990s.

http://www.gotobelfast.com/index. - November 12, 2005 at 4:45 pm #767257

Praxiteles

ParticipantAfter a little digging, it appears that Ludwig Oppenheimer worked on several major projects in Ireland:The Dublin Museum (1890); Cobh Cathedral (1892); Sts Augustine and John, Thomas Street, Dublin (c.1899); Newry Cathedral (1904-1909); Redemptorist Church, Limerick (1927); Sts. Peter and Paul, Clonmel (??); St. Mary’s, Nenagh (1910); the Honan Chapel, UCC,Cork (c.1915); Clonakilty; Fermoy; Midleton; Kilmallock. Interestingly, George Ashlin was involved in all of the above mentioned projects (except the Honan Chapel and Dublin Museum) and seems consistently to have retained Ludwig Oppenheimer to carry out mosaic work.

- November 12, 2005 at 5:26 pm #767258

Neo Goth

ParticipantSo the proposed changes necessitate the destruction of the mosaic floor of the cathedral but what will be put there in its place? Does the architect favour the bathroom tile model of the cathedral in Killarney?

- November 12, 2005 at 5:43 pm #767259

Praxiteles

ParticipantA pastiche job is proposed incorporating salvage from the present central mosaic and some matching glories imported from the Domus Dei people who similarly obliged -albeit much less radically- in Newry (1992). Apart from that, no specifics have been outlined by Cathal O’Neill for the replacement.

- November 12, 2005 at 6:24 pm #767260

MacLeinin

ParticipantI thought that the Parish Church in Nenagh was by Walter Doolin, not Ashlin.

- November 12, 2005 at 6:33 pm #767261

Praxiteles

ParticipantYes, you are correct. The parish church in Nenagh is by Walter Doolin. Ashlin was the assessor for the competition and chose Doolin’s submission. Walter Doolin had also been George Ashlin’s pupil. Jermey WIlliams in his Companion Guide to Architecture in Ireland 1837-1921 describes Doolin’s as a conservative architecture derived from Ashlin. The interiors of his churches “come as a welcome relief due to his determination to create a multi-coloured paradise out of the chancels, relying not only on frescoes, and stained glass but also on mosaics, and wrought iron grilles, painted and decorated”. G. Ashling completed Nenagh in 1910. You might also note that Walter Doolin is also the architect for the parish church in Charleville which explains Oppenheimer’s mosaic work there.

- November 12, 2005 at 6:39 pm #767262

MacLeinin

ParticipantThanks for that.

Can anyone confirm that the mosaic work in Charleville – that can still be seen – is by Oppenheimer. - November 12, 2005 at 6:48 pm #767263

Gianlorenzo

Participant:confused: At present the Sedelia has been removed from right hand Sanctuary screen and is now free standing in Sanctuary and a dining chair put in its place.

Can anyone explain who this can happen since the building was listed as a protected structure and is the subject of a Covenant with the Heritage Council

- November 12, 2005 at 7:16 pm #767264

Peter Parler

ParticipantThanks for the photo, Gianlorenzo. I’d have assumed you were joking about the dining chair!

- November 12, 2005 at 7:43 pm #767265

Praxiteles

ParticipantThey cannot surely have been so ignorant as to attach that awful piece of metal to the back of one of the sedilia!!

Does the genius who perpretrated this bit of hooliganism not realize that this sedilia is based on the classical faldisterium which was taken by the pro-Consuls on their missions outside of Rome as a symbol of their authority and jurisdiction? Does he not know that the pro-Consuls sat on it to give judgement and that its assumption into Christian usage is just one example of what is now described as “inculturation”?

- November 12, 2005 at 7:45 pm #767266

Gianlorenzo

ParticipantCan anyone tell me how I post a photograph directly onto the tread? I am having terrible trouble with attachments.

- November 12, 2005 at 9:39 pm #767267

Gianlorenzo

ParticipantSorry Praxiteles for the incorrect spelling of sedilia on the picture caption!!!

- November 12, 2005 at 10:33 pm #767268

Gianlorenzo

ParticipantI am still having trouble with attachments. The byte space is too limited. Help

- November 12, 2005 at 10:40 pm #767269

Neo Goth

ParticipantI suppose hooligans always have a few iron bars to spare … I suppose this is a form of regressive inculturation.

- November 12, 2005 at 10:49 pm #767270

MacLeinin

ParticipantNeo Goth. Given the etymology of the discription ‘Gothic’ I do believe that it is His Lordship Bishop Magee who should bear that tag rather than your good self

- November 12, 2005 at 11:20 pm #767271

Neo Goth

ParticipantWe’ve been trying to disavow the Vandals for centuries who’ve been giving us a bad name. It’s easy to spot them though, they usually go around with iron bars and sometimes they try to disguise and hide their iron bars in the most unusal of places.

- November 12, 2005 at 11:48 pm #767272

Gianlorenzo

ParticipantMore Pictures.

A is the current Sanctuary floor which is to be dug up.

B is the lower chancel floor and altar rails which are to be dug up and stored!!!!

C is a view of the Chancel Arch from the southwest.The vandals are truly among us.

- November 13, 2005 at 12:28 am #767273

descamps

ParticipantA recent picture of the chancel in St. Colman’s Cathedral, Cobh.

- November 13, 2005 at 1:44 am #767274

Gianlorenzo

ParticipantOne passing shot before I retire. Attached is an example of the quality of ‘replacement/restoration’ work that has been carried out in St. Colmans with the help of over €170,000 (£ equivalent) of Heritage Council grants plus the hundreds of thousands donated by the people of Cobh and the Diocese of Cloyne for the restoration project. 🙁

- November 13, 2005 at 2:25 am #767275

Praxiteles

Participant“…Gothic adventurers crowded so earerly to the standard of Radagaisus, that, by some historians, he has been styled the King of the Goths…Alaric was a Christian and a soldier, the leader of a disciplined army; who understood the laws of war, who respected the sanctity of treaties; and who had familiarly conversed with the subjects of the empire in the same camps and the same churches. The savage Radagaisus was a stranger to the manners, the religion and even the language of the civilised nations of the South. The fierceness of his temper was exasperated by cruel superstition; and it was universally believed that he had bound himself by a solemn vow to reduce the City into a heap of stones and ashes, and to sacrifice the most illustruous Roman senators on the altars of those gods who were appeased by human blood….Comitantur euntem Pallor, et atra Fames; et saucia lividus ora Luctus; et inferno stridentes agmine morbi”. (Edward Gibbon, Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, chapter 31).

- November 13, 2005 at 3:20 am #767276

Praxiteles

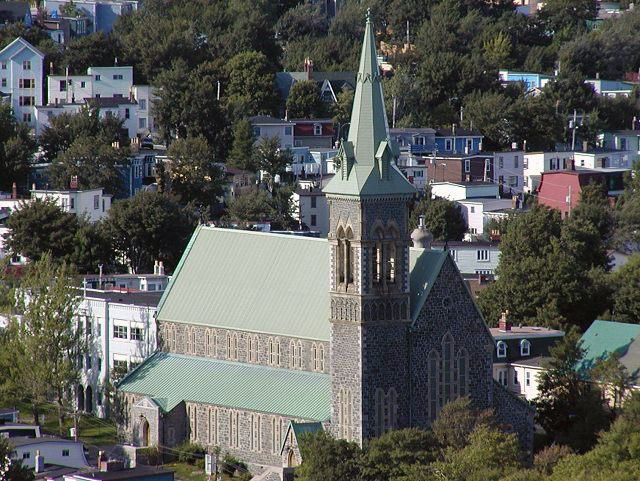

ParticipantTo complete the newly acquired picture gallery, I thought you might like to have the enclosed picturesque photographic study of the South elevation of the exterior of St. Colman’s Cathedral, Cobh, Co. Cork

- November 13, 2005 at 1:14 pm #767277

Peter Parler

Participant(#52) Much as one might regret the hooliganism perpetrated on that sedilia, Praxiteles, no one who has tried sitting on one for any length of time could possibly begrudge an aging Pro-Consul the back support. Some of them, as you know, are nowadays quite spineless.

- November 13, 2005 at 7:25 pm #767278

MacLeinin

ParticipantCould there be hope for Killarney at last!!! Did you all see the article below in the Sunday Indo. today?

Magnificent artifacts to return to Gothic Cathedral

JEROME REILLY

MAGNIFICENT artefacts removed from Pugin’s Gothic masterpiece, St Mary’s Cathedral in Killarney could be re-installed, if a historian and antiques expert has his way.

The cathedral was finally completed in the Twenties following some 80 years of construction work.

But in the early Seventies, under the direction of Bishop Eamon Casey, the cathedral was remodelled to take account of changes in the liturgy demanded by Vatican II.

That included the removal of a dozen brass chandeliers and a number of magnificent brass candelabra which then fell into private ownership.

Those artefacts were recently purchased by local historian and antiques dealer Maurice O’Keeffe who was very much aware of their historic provenance.

“I have restored one of them and they are magnificent. I would be more than willing to let the church have them for exactly the same amount I paid for them so they could be re-installed,” he said.

The cathedral was designed by Augustus Welby Pugin and is renowned for its Gothic proportions.

Work commenced in 1842 but stopped between 1848 and 1853 because of the famine, when the building was used as a hospital.

The Californian Redwood tree in the grounds was planted after the famine in memory of the children buried underneath. Pugin died insane in Ramsgate in 1885. - November 13, 2005 at 9:08 pm #767279

Praxiteles

ParticipantWell, just as civilization is sowing the first seeds of a serious “restoration” work in Killarney, the pall of Bishop Magee’s medieval darkness still hangs over Cobh cathedral. The Bishop of Kerry may not realize just how luck he is still to be able to locate the original fittings of Killarney cathedral. Have we come full circle?

- November 13, 2005 at 9:17 pm #767280

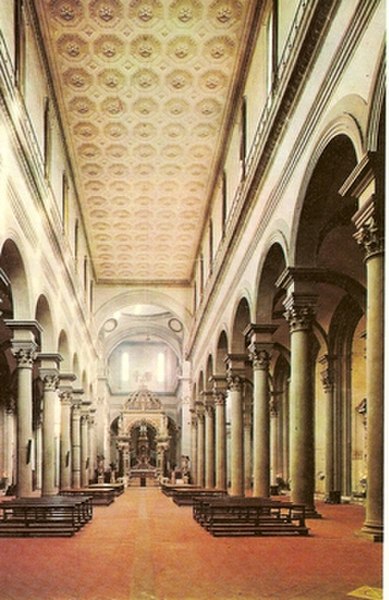

Praxiteles

ParticipantFor the purposes of contrast…… While much can be commented on, the floor is particularly noteworthy – especially after 35 years of wear and tear. The only remaining portion of the original floor is to be found in the Lady Chapel. Its destruction was staved off by the efforts of the redoubtable Beatrice Grovner who stood on her patronal rights as heiress to the Earls of Kenmare who are buried in the crypt underneath. The architect for the Killarney project was Dan Kennedy.

- November 13, 2005 at 9:38 pm #767281

Praxiteles

ParticipantPerhaps Paul Clerkin might be able to provide a picture of St. Macartan’s before Joe Duffy was let loose on the building. I am told that a confessional in bee-hut form was subsequently introduced. While most would regard this as eccentric, not the good bishop who was eloquent about the early Irish penitentials and the monastic cells on Skellig Michael…… The architect in this case was Gerald MacCann, if memory serves me correctly.

- November 13, 2005 at 10:03 pm #767282

MacLeinin

ParticipantO’Neill’s proposals for Cobh Cathedral look more and more like re-heated soup. -see attachment.

There is a very obvious lack of imagination in both clerical and architectural circles in Ireland.

😮 Just where do these clapped out prototypes come from? - November 13, 2005 at 10:44 pm #767283

Neo Goth

ParticipantThe sanctuary furnishings in the cathedral in Monaghan look like a bathroom set. Does the ambo have hot and cold taps? Will the new liturgical furnishings for the cathedral in Cobh be the same? There doesn’t seem to be any details given about these.

- November 14, 2005 at 2:02 am #767284

Gianlorenzo

ParticipantTwo more views of the O’Neill’s foolishness courtesy of http://www.foscc.com :p

- November 14, 2005 at 2:17 am #767285

Praxiteles

ParticipantThe photomontage could pass for Monaghan had the high altar there not been demolished. All that seem to have been done in this “adaptation” was to knock off the hard edges of Monaghan and supply soft curves and semicircles.

- November 14, 2005 at 3:32 am #767286

Neo Goth

Participant - November 14, 2005 at 4:33 am #767287

Neo Goth

ParticipantWill what happened to the cathedral in Monaghan be the fate of St. Colman’s?

The following is the ‘rationale’ from the official website of Clogher diocese for the iconoclastic ‘refurbishment’.

A radical rearrangement and refurbishing of the Cathedral was begun in 1982 to meet

the requirements of the revised Liturgy.The people of Monaghan were told a big lie… people of Cobh beware this lie is long past its tell by date!

The pic below is the architect’s view of the ‘refurbished’ sanctuary of St. Colman’s

- November 14, 2005 at 6:17 pm #767288

Praxiteles

ParticipantA shocked collegue thought that the “remodelled” sanctuary in Monaghan looked for all the world like a childrens playground!!

- November 14, 2005 at 6:55 pm #767289

MacLeinin

ParticipantIT IS a playground – for wayward ‘children’.

- November 15, 2005 at 3:35 pm #767290

Peter Parler

Participant52 / Praxiteles, I am still thinking about those Proconsuls. Did you know that it was the Dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (http://la.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sulla) who decreed in 80 B.C. that the Provinces were to be governed by ex-Consuls? It was a way of getting them out of Rome once they had outlived their usefulness. Apparently they were appointed for a maximum of five years – but of course few of them survived that long. It was never meant that they should! See http://la.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proconsul

- November 15, 2005 at 6:29 pm #767291

Praxiteles

ParticipantRe Jerome Reilly’s article reproduced in no. 65: it should be noted that A.W.N. Pugin died, at the age of 40, on 14 September 1852 as a result, not of insanity, but probably of the effects of mercury poisoning cf. Rosemary Hill, Augustus Welby Northmoe Pugin: A Biographical Sketch, in A.W.N. Pugin:Master of Gothic Revival,Yale University Press, New Haven and London 1995.

- November 15, 2005 at 9:34 pm #767292

Praxiteles

ParticipantFor the picture gallery: a view of the west elevation of St. Colman’s Cathedral Cobh.

- November 15, 2005 at 9:53 pm #767293

Praxiteles

ParticipantAnother view of the interior of St. Mary’s Cathedral, Killarney from c. 1899.

- November 16, 2005 at 12:26 am #767294

GrahamH

ParticipantA magnificent ‘strong’ building: very imposing and located on a fine site – indeed one of the best aspects of the building is its environment.

- November 16, 2005 at 7:44 am #767295

Neo Goth

ParticipantAcross the harbour from Cobh Cathedral the North Cathedral in Cork was vandalised by the liturrgical refurbishers,,,

Unfortunately this is another classical example of the after being worse than the before..BEFORE

AFTER

- November 16, 2005 at 3:53 pm #767296

Praxiteles

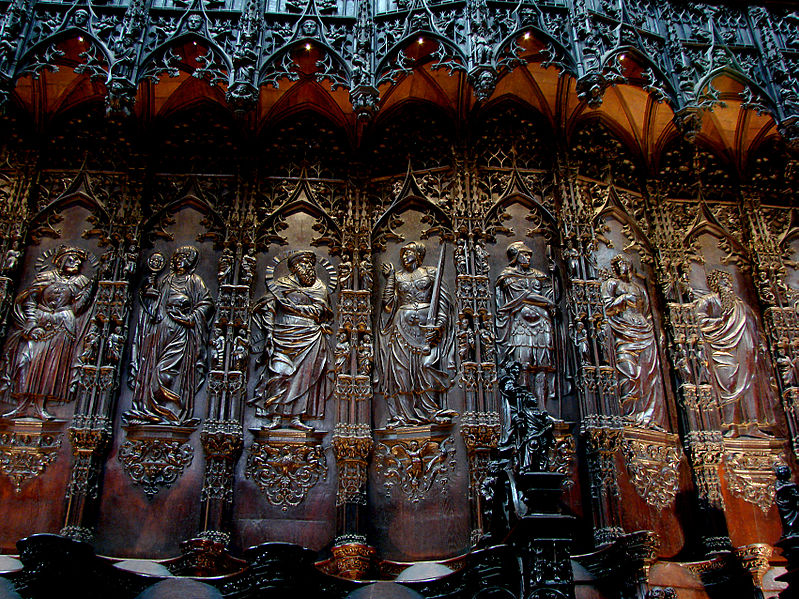

ParticipantAfter Killarney, Armagh must be one of the most questionable attempts at “reordering”. The building was begun in 1840 to designs by Thomas Duff of Newry but suspended because of the famine. It was resumed to plans by JJ McCarthy and the interior completed by G.C. Ashlin. Circa 1980, Ashlin’s original sanctuary was all but destroyed by an already liturgically dated effort by Liam McCormack. Casulties of the iconoclasm include Cesare Aureli high altars, Beakey’s pulpit, the roodscreen, M. Dorey’s choir stalls, and the 1875 Telford organ.

- November 16, 2005 at 4:15 pm #767297

Praxiteles

ParticipantAnother example for the list of “reorderings” that should not have happened is the Cathedral of the Assumption in Tuam, Co. Galway. Begun in 1837 by Archbishop John McHale to ambitious plans by the little known Dominic Madden, it was regarded as one of the finest examples of early Gothic revival in Ireland. The fine window behind the (demolished) high altar is by Michael O’Connor (1860). An iconoclastic outburst in 1979 saw the destruction the original baldichino, transcept altars, pulpit and altar rails. A further effort was made in 1991 under the direction of Ray Carroll which saw the demolition of the high altar, and the implantation of a misplaced faux roodscreen which succeeded in obscuring the lower part of O’Connor’s window. The great Lion of the West lies beneath all this, his crypt in-filled with the rubble of his own creation. One commentator described the overall present effect as reminicent of a set for a re-run of Snow White and the seven dwarfs.

- November 16, 2005 at 10:46 pm #767298

Praxiteles

ParticipantDominic Madden’s Cathedral of St. Peter and St Paul in Ennis is another example of liturgical adaptation gone wrong. Begun in 1828 and completed by 1842, the decoration of the interior was assigned to JJ McCarthy who is responsible for the internal pillars, with traceried spandrels, and galleries. The building was re-decorated in a renovation begun in 1894 under the direction of Joshua Clarke, father of Harry Clarke. The fresco of the Assumption, which stood behind and above JJ McCarthy’s (demolished) high altar, is by Nagle and Potts. Ennis Cathedral was one of the first in the country to undergo “reordering” according to a perceived need to bring it into conformity with the liturgical requirements of the Second Vatican Council. The guiding light in this was Michael Harty, dean of Maynooth College and subsequently Bishop of Killaloe. Although not an academic nor a trained liturgist , and more at home in teaching rubrics, Michael Harty acquired a reputation in church architecture circles for boldly going where no one went before and exercised a main morte on the design /execution of many Irish churches from the seventies on – his first being the ruination of St Mary’s Chapel in Maynooth College. Andy Devane was the architect for the Ennis “reordering”, backed up by the subtle aestesia of Enda King. The new altar and ambo were done in the erratic natural boulder style highly reminiscent of the de Bello Gallico‘s descriptions of druidic ritual. As in many of the Irish Cathedral “reorderings”, the noteworthy dissapearance of the Chapter Choir stalls is significant.

- November 16, 2005 at 11:26 pm #767299

Praxiteles

ParticipantThe red rosette in the outré class of the Irish cathedrals’ reordering stakes must surely go to St. Peter’s Cathedral in Belfast. Designed by Jeremiah Ryan McAuley, the foundation stone was laid in 1860. The building opened for public worship in 1866. The present refurbishment was undertaken by the late Cardinal Cahal Daly in 1982 and concentrated to a peculiar degree of obsession on the doctrinaire insertion of the Cathedra in basilical fashion behind a miniscule altar. All major components were executed in Cardinal Daly’s preferred wooden types resulting in a precarious dependence on aesthetically poised flower arrangements to relieve a brooding monotony. Again, the Cathedral Chapter has been unseated and Choir Stalls are nowhere to be seen. “Further refurbishment is planned so that St. Peter’s Cathedral will be an adornment in the regeneration currently taking place in inner Belfast”. Nobody seems to want to own up for all of this.

- November 16, 2005 at 11:28 pm #767300

Gianlorenzo

ParticipantHas some discreet cloning taken place in architectural circles in Ireland. From what I have seen so far it is all a variation on the same theme. Not only that, it is a theme that is pursued regardless of the setting. Maybe we should have a poll as to which is the most insensitive re-ordering to date. Any takers?

- November 16, 2005 at 11:37 pm #767301

MacLeinin

ParticipantDoes anybody know which architect is responsible for the re-ordering of St.Peters in Belfast? Was it perhaps Ray Carroll?

- November 17, 2005 at 12:28 am #767302

MacLeinin

ParticipantMy vote on the worst re-ordering to date goes to Tuam. 😮

- November 17, 2005 at 1:16 am #767303

Gianlorenzo

Participant😎

Thought that this comment was worth sharing. One only hopes that this state of affairs can be maintained.TAKING STOCK OF OUR ECCLESIASTICAL HERITAGE

The Heritage Council 1998John Maiben Gilmartin.

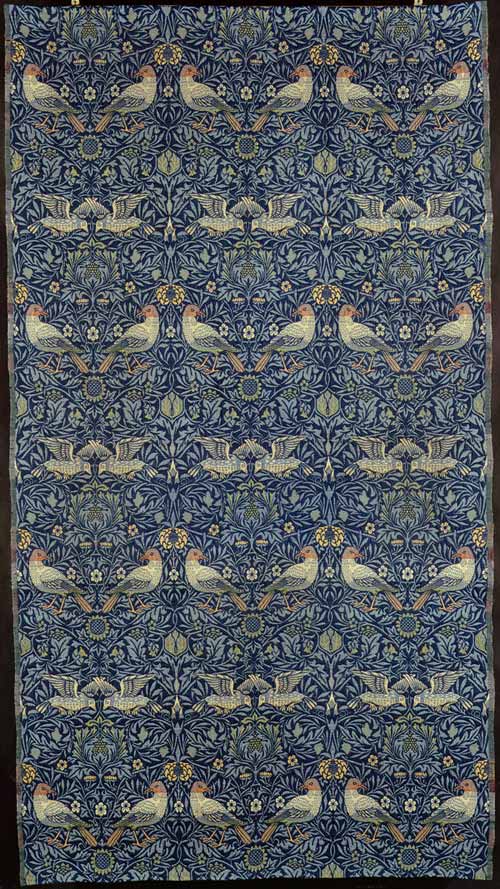

Ecclesiastical Works of ArtHowever, the positive and the good must not be disregarded. Mention should be made of initiatives of high merit, such as the maintenance of Cobh Cathedral both externally and internally. This building has an outstanding interior which almost alone of Irish nineteenth century cathedrals survives intact. The beneficent authorities at Cobh have also seen that their fine collection of textiles has been superbly restored and conserved.

- November 17, 2005 at 1:26 am #767304

the bull

ParticipantKillarney, Monaghan, Armagh, Tuam,Ennis,Belfast,………….. My God how do they get away with it.

This must not happen in Cobh

- November 17, 2005 at 1:32 am #767305

the bull

ParticipantRE no 89 I agree my vote goes to Tuam for the worst re-ordering to date. With Ennis as a close runner up.

Killarney is in a category all of its own - November 17, 2005 at 1:35 am #767306

Gianlorenzo

ParticipantRe.#91 They have been getting away with it because the only ones to object are their own parishioners and in the stratospheric world of architects and clerics they do not count. Fortunately in Cobh there is a very organised and informed opposition who hopefully will prevail.They have a wonderful website -www.foscc.com

- November 17, 2005 at 1:50 am #767307

Praxiteles

ParticipantAnother boring application of the hackneyed pastiche formula – St. Eugene’s Cathedral in Derry. Begun in 1851 to designs by an unknown and eventually to plans of JJ McCarthy, St. Eugene’s was consecrated in 1873. The spire designed by G.C. Ashlin, added in 1899, was completed in 1903. The glass is by Mayer of Munich. Liam McCormack of Armagh Cathedral fame also struck in Derry in 1975.

- November 17, 2005 at 2:06 am #767308

MacLeinin

ParticipantDerry (#94) looks positively dangerous. Has anyone fallen off yet?

- November 17, 2005 at 5:05 pm #767309

Praxiteles

ParticipantLongford Cathedral was widely regarded as Ireland’s finest example of a neo-Classical cathedral. The original architect was John Benjamine Keane with subsequent contributions from John Bourke (campanile of 1860) and the near ubiquitous G.C. Ashlin who is responsible for the impeccably proportioned portico (1883-1913) commissioned by Bishop Bartholomew Woodlock of Catholic University fame. The internal plaster work is Italian as were the (demolished) lateral altars. It was opened for public worship in 1856. In the 1970s a major re-styling of the sanctuary was undertaken by Bishop Cathal Daly who employed the services of Wilfred Cantwell and Ray Carroll. J. Bourke’s elaborate high altar altar and choir stalls were demolished and replaced by an austere arrangement focused on a disproportionately scaled altar. The results, which have not drawn the kind of universal criticism reserved for Armagh and Killarney, nevertheless leave the interior of the building without a natural focus. The insertion of tapesteries between the columns of the central apse was an attempt to fill the void and would be used again to solve a similar problem in the Pro-Cathedral in Dublin. The absence of choir stalls is to be noted as is the relative obscurity of the Cathedra – the very raison d’etre for the building.

- November 17, 2005 at 5:11 pm #767310

Paul Clerkin

Keymaster@Praxiteles wrote:

After Killarney, Armagh must be one of the most questionable attempts at “reordering”. The building was begun in 1840 to designs by Thomas Duff of Newry but suspended because of the famine. It was resumed to plans by JJ McCarthy and the interior completed by G.C. Ashlin. Circa 1980, Ashlin’s original sanctuary was all but destroyed by an already liturgically dated effort by Liam McCormack. Casulties of the iconoclasm include Cesare Aureli high altars, Beakey’s pulpit, the roodscreen, M. Dorey’s choir stalls, and the 1875 Telford organ.

More on the interior of Armagh

http://www.irish-architecture.com/buildings_ireland/armagh/armagh/st_patricks_interior.html

- November 17, 2005 at 5:14 pm #767311

Paul Clerkin

Keymasterand no one has mentioned St John’s in Limerick yet

- November 17, 2005 at 5:32 pm #767312

johannas

ParticipantOr what about Wexford, does anyone know if this Cathedral of Pugin design has been laid bare to the vandals?

- November 17, 2005 at 5:45 pm #767313

Mosaic1

ParticipantDear thread contributors,

I am ‘Mosaic1’ and I am new to your discussions, which are very interesting to me. You have been discussing the work of Ludwig Oppenheimer Ltd. in relation to Cobh & elsewhere and Iyou might like to know that there are 2 additional churches that may contain their work – St. Fintan’s, in Taghmon, Co. Wexford, and St. Mary’s, in Listowel, Co. Kerry.

With scholars and mosaic enthusiasts in Ireland and the U.K., I have been researching the firm for some time now, prompted initially by the apparent, and puzzling, absence of information on them and their work. We now know a good deal more about the firm and the people and are hoping to have a seminar and to publish a book on them and their works. The firm was founded in 1865 in Manchester and operated until 1965. It’s mosaics are known in Ireland, England, France and 1 in the U.S. Bizarrely for a Manchester based firm, most of their presently known work is in Ireland, so much remains to be learnt about their work in Britain.

If anybody has any information or knows of any possible sources of such, I’d be very grateful to hear from them.

Kind regards, and many thanks in advance for your help,

‘Mosaic1’

- November 17, 2005 at 5:58 pm #767314

Praxiteles

ParticipantRe n. 98: I am glad you raised the case of Limerick which has undergone a very recent restoration and “make over” of the interior, especially of the sancturay. The original architect here was Philip Charles Hardwick who had been retained by the Earl of Dunraven to build Adare Manor. It was constructed 1856 – 1861 and consecrated in 1894. From a distance, the spire (280 feet) makes a very memorable impression on the flatness of the Limerick plain. The Cathedral interior is a fine example of the effective use of light and is one of its principal features – nowadays not so clearly evident because of over-illumination. The high altar, throne, and pulpit were made by the Belgian firm of Phyffers. Although re-arranged by J.J. O’Callaghan in 1894, they survived into the 1980s when, unfortunately, the throne was removed and resited in the vacuum left by the altar mensa which had been moved “nearer to the people”. The tabarnacle in the reredos was abandoned and its door replaced by the heraldic achievement of the then Bishop. In placing the throne in the site intended for the mensa of the altar, little account was taken of the surprising (if not incongrous) effect of seeing the successor of St. Munchin seated on a throne at either side of which was clearly emblasoned a strophe of the Trishagion. A rood beam survived with its figures into the 1980. In the latest round, the choir stalls seem to have survived.

- November 17, 2005 at 7:45 pm #767315

Praxiteles

ParticipantSt. Mary’s Cathedral, Kilkenny, designed by WIlliam Deane Butler, was begun in 1843 and completed in 1857. Its neo-Gothic style is heavily Norman in inspiration and can be easily compared with St. Jean de Malte in Aix-en-Provence, St-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume in Provence or indeed with many of the pure creations of the Norman displacement in central and southern Italy – such as the abbatial church at Fossanova in Latium, Sant’Eligio in Naples, and San Lorenzo Maggiore in Naples. The decoration of the interior of Kilkenny’s St. Mary’s is by Earley and Powell and was brought to completion in 1865. This firm was responsible for the ceiling painting of the chancel, the glass, the high altar fittings and lightings. The mosaic work is by Bourke of London and the chancel murals by Westlake. In the 1970s, the socially minded Bishop Birch instigated, in the diocese of Ossory, an iconoclasm worthy of the emperor Leo III, a martial pesant from the mountains of Isouria whose hatred of images was largely inspired by an incomparable ignorance of both sacred and profane letters. Kilkenny cathedral, fortunately, escaped the worst ravages and retains its (albeit redundant) High Altar which was purchased in Italy. The altar rails (alas no more) and the altar of the Sacred Heart were the work of James Pearce. A diminuitive and out of scale altar was placad under the crossing and a new cathedra -redolent of Star trek – installed. The contour of this impianto is remarkably similar to the one now proposed for Cobh cathedral. Perhaps the greatest thing that can be said for this “reordering” is that it can (and will) eventually be removed leaving the building more or less as concieved by none too mean an architect.

So far, nobody wishes to claim responsibility for the effort.

- November 17, 2005 at 9:32 pm #767316

Praxiteles

ParticipantThe Cathedral of the Assumption of Our Lady in Thurles, Co. Tipperary, boasts of being Ireland’s only 19th century cathedral to have been built in the neo-romanesque style. Building commenced in 1865 to plans by JJ McCarthy who relied very heavily on North Italian or Lombard prototypes, modelling the facade on that of the Cathedral in Pisa, and, succeeding to some extent in conveying the spacial sense of the Cathedral complex in Pisa with his free standing baptistery and tower. The Cathedral was consecrated by Archbishop Croke on 22 June 1879. Archbishop Croke replaced JJ McCarthy with George C. Ashlin as architect for the remaining works which included the decoration of the interior on which no expense was spared. The ceiling, designed by Ashlin, was executed by Earley and Powell. The same company are also responsible for the galss and some of the sculpture work, the more important elements of which were executed by Pietro Lazzarini, Benzoni and Joseph O’Reilly. Mayer of Munich also supplied glass as well as Wailes of Newcastle. The most important item, however, in the Cathedral is the Ciborium of the Altar by Giacomo della Porta (1537-1602). This had originally been commissioned for the Gesù in Rome in 1582 by Cardinal Alessandro Farnese. The same Giacomo della Porta built the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica 1588/1590 and finished the lantern in 1603. The altar from the Gesù was acquired by Archbishop Leahy while in the City for the First Vatican Council in 1869/1870. Reordering work began here in 1979. The altar rails have given way in the face of a projection into the nave. Unbelievably, the High Altar has been dismantled and its mensa separated from the della Porta ciborium which is now relegated to an undescript plinth. The original stencilled work disappeared in 1973. As with Longford and the Pro Cathedral, the removal of the High Altar leaves the building without a focus, the present dimension and location of the Ciborium not being to the scale of the building. The temptation to hang banners in the apse has not been resisted.

It is difficult to ascertain the architect responsible for the current interior of Thurles Cathedral.

- November 17, 2005 at 11:53 pm #767317

Praxiteles

ParticipantThe Cathedral of St. Patrick and St. Colman, Newry, Co. Down is a composit building in a neo Gothic idiom developed in three main phases bewteen 1825, when it was begun to plans by Thomas Duff, extended between 1888 and 1891, futher extended between 1904 and 1909, and finally completed in 1925. The only part that can be reasonably described as Victorian are the transepts (1891); high Altar, pulpit and belfry (by Ashlin). The decorative scheme was drawn up by Thomas Hevey and executed by G.C. Ashlin who alsoextended the nave and chancel in 1904. The sanctuary was re-ordered in 1990 by extending the dais into the nave, and placing the mensa of the original altar under the crossing. The pulpit appears to have survived but not the altar rails. The reredos of the altar was needlessly divided into three section for reasons not easily or immediately fathomed. The present tri-partite re-constructed reredos is slightly reminiscent of the revolving stage scenes of an 18th century petit theatre. The most remarkable implant of the reordering must be the throne in a neo Gothic idiom. Curiously, it is probably the largest throne created in any re-ordering in Ireland -for what is one of the smallest dioceses in the country. Among the conoscenti, it is often deferred to as a “model” for what could be done in Cobh Cathedral – a building far outstripping Newry in its superiority of conception, execution and stylistic unity. Again, this cathedral is bereft of Choir Stalls.

- November 18, 2005 at 2:12 am #767318

GrahamH

ParticipantThanks for all the pictures Praxiteles – partiicularly Longford, what a gem of a building. Those columns are magnificent!

How disturbing to see all of these reorderings in black and white – whatever about the removal of architecturally significant features, but to then install bathroom showrooms as liturgical and architectural focal points of these splendid buildings is nothing short of criminal.Another by Duff, and whilst not (quite :)) a cathedral, and not as opulent as others featured, St. Patrick’s in Dundalk has had the most horrendous rubbish thrown up in the sanctuary. I don’t remember what was here before the ‘changes’, but in its place has been put what can only be described as an altar table from Homebase fronted by an 8×4 sheet of MDF with laser cut gothick arches, bright verdigris paint and backlit with a florescent tube:

Luckily the worst of it is concealed here beneath the altar cloth. It beggars belief when you see it up close – looks like a cartoon plonked into the ‘real world’.

Also the throne looks like it was a nicked from a 1980s country house hotel, whilst the timber lecturn with ‘feature panel’ is equally inappropriate in an exclusively marble environment.

On the upside, I believe St. Patrick’s also has mosaics by Oppenheimer, just not sure which particular ones.

I dread to think what was there before the timber-n-carpet conference stage was introduced 🙁 - November 18, 2005 at 2:57 am #767319

Praxiteles

ParticipantThe Cathedral of St. Brendan in Loughrea, Co. Galway was begun in 1897 to plans drawn up by William Byrne and completed by 1902. In size, it is quite modest and, exteriorally, not much different from many churches then being buit in Ireland. Byrne was commissioned to bulit a church in the neo Gothic idiom, having a nave, absidal chancel, lean-to isles, a shallow transcept and a spire. The interior, however, is another matter. By some strange providence, the interior became a veritable icon of the Celtic revival movementin terms of sculpure, above all glass, metal work and wood work. This gem was the product of a partnership of interest in the Celtic Revival shared by Fr. Jeremiah O’Donovan, who was given charge of the Loughrea cathedral project, and by Edward Martyn (benefactor of the Palestrina Choir in the Pro-Cathedral). John Hughes was commissioned to do the sculpture for the interior -including the bronze relief of Christ on the reredos of the High Altar and a marble statue of Our Lady. Michael Shortall was commissioned to execute a statue of St. Brendan and the corbels. He is also responsible for the scenes from the life of St. Brendan on the capitals of the pillars. Designed by Jack B. Yates and his wife Mary, the ladies of the Dun Emer guild embroidered twenty four banners of Irish saints. The same studio provided Mass vestments etc.. The stained glass is by An Tur Glaoine (opened in 1903) under the direction of Alfred Childe and Sarah Purser. Over the next forty years A. Childe, S. Purser and Michael Healy executed all of the glass. Michael Healy’s Ascension (1936) and Last Judgement (1937-1940) are amongst the Cathedral’s greatest treasures. Fortunately, the liturgical Boeotians have not yet managed to exact their vengence on this little gem. The High Altar, communion rails, and pulpit are all still in tact – though the inferior quality of the modern liturgical furnishings inserted into the original organic whole is patently obvious.

- November 18, 2005 at 3:29 am #767320

Gianlorenzo

ParticipantAnother view of St. John’s in Limerick. The more I look at the sanctuary floor the more I am reminded of something from a Harry Potter movie. 😮

- November 18, 2005 at 3:39 am #767321

Gianlorenzo

ParticipantFor Praxiteles re #84 Tuam Cathedral. Here is a shot of the original sanctuary showing baldachino 🙂

and one of the side altars. - November 18, 2005 at 4:34 am #767322

Gianlorenzo

Participant“……… St. Mel’s Cathedral, begun to the design of Joseph Keane in 1840. While the portico lacks the sophistication of Keane’s great Dominican Pope’s Quay Church in Cork, the interior, by contrast, is now regarded as noblest of all Irish Classical church interiors. It is designed in the style of an early Christian basilica, with noble Grecian Ionic columns and a curved apse. It also shares the remarkable distinction of being the only major Catholic Church in Ireland to have actually been improved by internal reordering, when the fussy later altar was removed and replaced by a simple modem table altar, which accords harmoniously with the early Christian style of the interior. The tower and portico give a striking approach to the town from Dublin.”

(An Taisce)Is this true? I have been unable to find any photographs of St. Mel’s so am unable to judge. Does anyone have before and after shot so we can decide.

- November 18, 2005 at 6:06 pm #767323

johannas

ParticipantWell Graham, at least St. Patrick’s in Dudalk still retains the beautiful italian altar rails and brass gates insitu and though the homebase altar is quite disturbing, the sanctuary hasn’t quite been turned into a disney ice rink!!!

- November 18, 2005 at 7:47 pm #767324

Praxiteles

ParticipantRe. post 109

It also shares the remarkable distinction of being the only major Catholic Church in Ireland to have actually been improved by internal reordering, when thee fussy later altar was removed and replaced by a simple modern table altar, which accords harmoniously with the early Christian style of the interior.Gianlorenzo wrote:“While the import of the above is not exactly clear, the idea that the modern undersized altar in Longford Cathedral “accords harmoniously” with the early Christian style of the interior is quite remarkable for its evident obliviouness to the findings of Christian archeology and the factual testimony of those Basilicas which still conserve their original spacial lay out. The result of Cathal Daly’s reordering of Longford is a modern construct derived from contemporary theories that has been brutally superimposed on a neo classical basilical context.

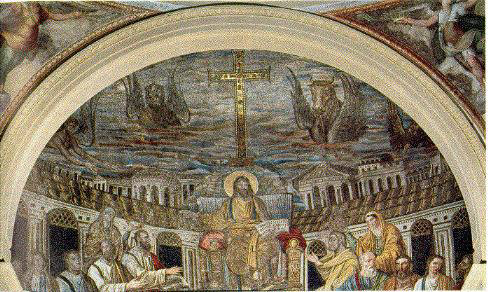

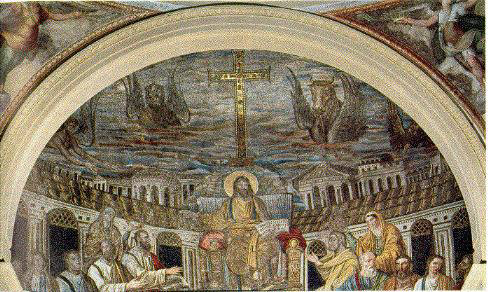

Were the reordering to have been conducted with the idea of reproducing or reinterpreting the prinicples underlying the spacial outlay of an early Christian Basilica, then the outcome would have been considerably different. It would have required emptying the nave of its benches]Solea[/I] extending one third of its length and marked off by barriers; a transverse barrier to mark off the Sanctuary; and the construction of a Ciborium or Baldachino over an altar on a raised dais. [See attachment 1 and 2]

In this system, the nave is reserved for the entry and exit of the Roman Pontiff and his attendants at least since the year 314when he was invested with the Praetorian dignity. When he arrived at the main door, his military or civil escort was shed; he processed through the nave with clergy any other administrative attendants until he reached the gate of the Solea at which point all lay attendants were shed; the lower clergy lined up in the Solea and remained there while the Pontiff, accompanied by the Proto Deacon of the Holy Roman Church and the Deacon of the Basilica accompanied him through the gate of the Sanctuary as far as the Altar where other priests or Bishops awaited him.

The laity were confined to the side isles; the matroneum (or womens’ side); and the senatorium (men’s side).

In Rome, two extant eamples of this spacial disposition illustrate the point: Santa Sabina which is partially intact [attachment 3]; but, more importantly, San Clemente which is well preserved [attachment 4].

Remarkably, the author who believes that the present interior lay out of Longford Cathedral somehow reflects that of an early Christian Basilica quite obviously has not read Richard Krautheimer’s Corpus Basilicarum Christianarum Romae and may not have been familiar with the same author’s Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture (Yale University Press). C. H. Kraeling’s The Christian Building (The Excavations at Dura Europos…Final Report, VIII, 2 (Yale University Press) and T. Matthew’s writings on the disposition of the chancel in early Christian Basilicas (Revista di Archeologia Cristiana, XXXVIII [1962], pp. 73ff. would certainly dispel any notion of even a remote connection between the early Christian Basilica and the current pastiche in Longford Cathedral.

- November 18, 2005 at 8:16 pm #767325

MacLeinin

Participant@Graham Hickey wrote:

What came of the appeal to the Supreme Court do you know Praxiteles?

I noticed that no one has attempted to answer your question. To the best of my knowledge the Friends of Carlow Cathedral lost their case in the Supreme Court – legend has it that one man lost his home as a result. I have tried following this story up on the web but there is nothing obviously available.

- November 18, 2005 at 8:54 pm #767326

Gianlorenzo

ParticipantSpeaking of Carlow, there was a story in the Carlow People today about some of the stained glass window being smashed.

“Smashed Cathedral windows will cost thousands to repair

A number of stained glass windows in Carlow Cathedral were broken last week in an attack which is expected to cost thousands of euro to repair.

The damage was done when a man threw a bin at a number of windows in the Cathedral last Wednesday night.

The motive for the attack is not known but Carlow Gardai apprehended a man at the scene.

This is the second attack on a church in Carlow in recent times as just over a month ago vandals threw kerbing through a number of windows in St. Mary’s Church of Ireland in Rathvilly.Assessors have now examined the damage to the Cathedral although according to administrator Fr. Ger Aherne they have not yet completed their examination.

‘We don’t know how much it will cost to repair them, there were three or four panels broken,’ he said. ‘The windows are quite old and we expect the cost will be substantial.” Carlow People 18/11/05The vandals have struck inside and out.!!!! 🙁

- November 18, 2005 at 9:44 pm #767327

Gianlorenzo

ParticipantInterior of Carlow. Does anyone have a view of the sanctuary before the changes?

- November 18, 2005 at 10:04 pm #767328

Praxiteles

Participantre #107

Looking at the floor in Limerick, there might be a vague suggestion of the Campidoglio in Rome – but I would not swear to it!

- November 18, 2005 at 10:14 pm #767329

MacLeinin

Participant🙂

Well done Praxiteles, I think you are correct. Is there some significance to the disign?

- November 18, 2005 at 10:42 pm #767330

Praxiteles

Participanten suivant la guerre….this time, we have the Cathedral of St.Eunan’s in Letterkenny, Co. Donegal, which, mercifully, has been subjected to a minimalist approach to “reordering”. It was the last of the major Gothic Revival cathedrals to have been built in Ireland. Begun to plans drawn by WIlliam Hague in 1891, it was completed in 1901 by his his partner T. F. McNamara. Here architecture “stained glass, sculpture, frescoes and mosaics are orchestrated into a triumphant unison”. The external sculpture is by Purdy and Millard of Belfast. The mosaic tiling of the choir is by Willicroft of Henley. The Pearse Brothers’ The High Altar, throne, pulpit (depicting the Donegal Masters), and communion rail all remain in situ. The glass is by Mayer of Munich and by Michael Healy whose work is to be seen in his windows of 1910-1912. The clerestory windows were designed by Harry Clarke. Great creidt is due the enlightened former Bishop of Raphoe, Dr. Seamus Hegarty, for this sensible approach to “reordering” and for his concern to preserve the integrity of the building.

- November 18, 2005 at 10:55 pm #767331

Praxiteles

ParticipantThe Cathedral of the Annunciation and St. Nathy, Ballaghadereen, Co. Roscommon is another example of a minimalist approach to “reordering” that has succeeded in conserving much of the original fabric and fittings of the building. Designed by Hadfield and Goldie, the foundation stone was laid in 1855 and completed in 1860. In the Early English idiom, a plan for a fan-vaulted ceiling had to be abandoned because of lack of funds. The external tower and spire are by W.H. Byrne. The glass was supplied by Earley, Mayer and An Tur Glaoine (the windows depicting St. John and St. Anne by Beatric Elvery). There are (and were) no choir stalls.

- November 18, 2005 at 11:11 pm #767332

Praxiteles

ParticipantThe Cathedral of the Most Holy Trinity in Waterford is the oldest Catholic Cathedral in Ireland. Begun to plans drawn up by John Roberts in 1793, the cathedral was completed c. 1800. The present sanctuary was installed in 1830; the apse and High Altar in 1854; and the Baldachino, supported by five corinthinan columns, in 1881. The pulpit, Choir stalls, and throne, designed by Goldie of London and carved by Buisine of Lille, were installed in 1883. The glass is mainly by Mayer of Munich – except for the chandeliers which are a gift of Waterford Glass Ltd.. A fairly minimalist reordering took place in 1977 during which the Choir Stalls were moved from their original position flanking the High Altar to a new position against the abse walls. The altar rails seem to have been removed and a moveable altar inserted.

- November 18, 2005 at 11:42 pm #767333

Praxiteles

ParticipantThe Cathedral of Our Lady Assumed in to Heaven and St. Nicholas, Galway, was the last Cathedral to be have been built in Ireland. Its patron was the formidable Bishop Michael John Browne and architect was John J. Robinson of Dublin. The builders were John Sisk. The foundation was laid in 1957 and the building was finished by 1965. The style, much criticized by the politically correct establishment, is certainly different from much of what was being built in Ireland at the time and reflects all sorts of eclectic elements borrowed from tpyes such as St. Peter’s in Rome, Seville, and Tuscany. The interior gives the impression of not having been completed and still lacks Choir Stalls, pulpit and perhaps even a proportionate High Altar in the apse. Those furnishings and fittings already in the building by 1965 have survived without any reordering.

- November 19, 2005 at 1:14 am #767334

Praxiteles

ParticipantAnother of the neo-classical Cathedrals, this time the Cathedral of St. Patrick and St. Phelim in Cavan town. Built to plans by W. H. Byrne of Dublin, it was begun in 1938 and completed in 1942. The tympanum of the portico contains figures of Christ, St. Patrick and St. Phelim by George Smith. The columns in the interior, the pulpit and statutes were supplied by Dinelli of Pietrasanta in Italy. The stations of the cross and the mural of the Resurreection are by George Collie. The High Altar is of green Connemara and red Midleton marble. The altar rails are in white Carrara marble. All of the original fittings and features are still in situ and reordering here has been minimalistic. Some of the glass was provided by the studios of Harry Clarke. In 1994 the Abbey Stained Glass company installed a set of eight stained glass windows made by Harry Clarke originally for the Sacred heart Convent in Leesons Street, Dublin between 1919 and 1934. Thee set depicts ST. Patrick and two princesses; St. Anne and the Blessed Virgin; St. Francis Xavier; St. Charles Borromeo; the Sacred heart and St. MArgaret Mary; St. Michael the Archangel; and the Apparition of Our Lady to St. Bernard. There do not appear to have been Choir Stalls.

- November 19, 2005 at 1:21 am #767335

Praxiteles

ParticipantThe Cathedral of Crist the King, Mullingar, Co. Westmeath, was built to plans drawn up by R.A. Byrne and WIlliam H. Byrne of Dublin. Work began in 1932 and the building was opened for public worship in 1936 and consecrated in 1939. Reordering here has been minimalistic with all of the main original fittings still in situ.

- November 19, 2005 at 3:37 pm #767336

Praxiteles

ParticipantThe Cathedral of St. Patrick, Skibbereen, Co. Cork, is the Cathedral church of the the diocese of Ross. It was buit between 1825/1826 and 1830 by the Rev. Michael Collins, subsequently Bishop of Cloyne and Ross. The Cathedral was built in a neo-classical style, and while modest in scale, is not without interest. The architect for Skibbereen was Michael Augustine O’Riordan, a remarkable man by any standards. Educated in the neo-classical style, he worked extensively in Cork City and County. Some of his churches include the North Chapel in Cork i.e. the Cathedral of St. Mary and St. Anne (1808), Blackrock Village (1818), Doneraile (1827), Millstreet (1836), Bantry (1837), Kinsale (1838), and Dunmanway (1841). In 1826, at the age of 42, he made profession as a Patrician Brother. Along with continuing building churches, convents and schools throughout Cork, he spent his time teaching in the schools for poor run by the brothers. Skibbereen Cathedral, fortunately, survived the rush to “reordering” and the worst phases of its consequent iconoclasm – partly due the sensitivity arising from the recent status of the diocese of Ross. It was only in very recent time that a fairly minimialist approach to reordering took place which saw the preservation of the High Altar but the loss of a portion of the fine altar rails and their gates in the face of the forward thrust into the nave all too familiar in Irish “reorderings”. The refurbishment and renovation of elements of the Cathedral in Skibbereen are by Wain Moorehead of Cork. The same refurbishment could usefully have removed the amplifiers adhering to the capitals of the columns at the chancel arch. Choir Stalls never appear to have been installed in Skibbereen.

- November 19, 2005 at 3:59 pm #767337

Praxiteles

ParticipantSt. Muredach’s Cathedral in Ballina, Co. Mayo was begun in 1828 and externally completed in 1831. The patron was John McHale, the young bishop of Killala. The architect was Dominic Madden who is also responsible for the cathedrals in Tuam and Ennis. Lack of funds and the famine inevitably induced changes to the original design. The spire was added in 1853 by John Benson. The project was finally completed in 1892. The ribbed ceiling, by Arthur Canning, is based on Santa Maria Sopra Minerva in Rome , the original painted decoration, however, has vanished. The glass is by Mayer of Munich. Of the High Altar, commissioned in Rome by Sir Kenelem Digby, only the mensa survives.

- November 19, 2005 at 6:52 pm #767338

Praxiteles

ParticipantThe Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, Sligo, has been dubbed by some as Ireland’s least loved Cathedral. It was built in a Germanic Romanesque style, quasi officially, and overwhelmingly, described as “Normano-Romano-Byzantine”. The Cathedral was built by Bishop Lawrence Gilloly to plans drawn up by George Goldie. WIth a seating capacity of 4,000, it has the largest capacity of any Cathedral in Ireland. The foundation stone was laid in 1868. The Cathedral opened for public worship in 1874 and was consecrated in 1897. The glass was supplied by Lobin of Tours. The High Altar is surmounted by a baldachino supported by columns of Aberdeen granite and was designed by Goldie. Benzoni is responsible for the large alabaster statue of Our Lady in the Lady Chapel. The Cathedral has undergone two major reorderings since it was built; one in 1970 which was minimalistic leaving all the main features in situ; and another more recently which saw a grille implanted in Goldie’s Baldachino which has the effect of obscuring the central focus of the building. Several prissy devices have been used to solicit a minimal attention for the new altar which has been placed in the main plain of the sanctuary. The fine altar rails have long disappeared and no Choir Stalls are to be seen.

- November 19, 2005 at 9:44 pm #767339

Gianlorenzo

Participant#124 Found these nice photos of stained glass in Ballina. 🙂

- November 19, 2005 at 11:44 pm #767340

Praxiteles

ParticipantSt. Aidan’s Cathedral, Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford was built to plans drawn by Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812-1852). It was one of a series of commissions obtained through the patronage of the Countess of John, sixteenth Earl of Shrewsbury, whose uncle, John Hyacinth Talbot was patron of the re-building of Enniscorthy church. Writing from Alton Towers to Talbot at Ballytrench on 14 May 1843, Pugin presented his plan for the a new church in Enniscorthy which would be build and “perfectly done by degrees …and make a glorious church”. He suggested “pulling down the farthest compartment of the present church and moving the altars….so that the whole of the present nave would serve for the church while this was being done” (Belcher, Collected Letters vol.II, p.52). With the completion of the chancel, and trancepts by 1846 and the nave build over the existing church, the original church was demolished in 1848. A central spire was finished in 1850 but subsequently rebuilt by JJ MCCarthy. While the building of St. Aidan’s opened new opportunities for Pugin, they were not however realised. Writing of Enniscorthy in 1850 he says. “There seems to be little or no appreciation of ecclesiastical architecture amongst the clergy. The cathedral I built at Enniscorthy is completely ruined. The bishop has blocked up the choir, and stuck an altar under the tower!!…it could hardly have been treated worse had it fallen into the hands of the Hottentots….It is quite useless to attempt to build true churches , for the clergy have not the least idea of using them properly. There is no rood screen as intended by Pugin. The High Altar was added by Pearce and Sharp to the designs of JJ McCarthy in 1857. The east window is probably by Hardmans of Bermingham to the designs of Pugin. Later glass is by Lobin of Tours and Mayer. A first modern reordering took place in the 1970s when a large granite altar was place under the corssing. This was replaced in 1996 in a more sensitive restoration of the building which saw a return of the original stenciling work. The 1996 Enniscorthy reordering was important for it signalled a change in reordering that exhibited a greater sensibility ot the integrity of the original contexts into which new elements were introduced. A similar approach would subsequently be taken to the more irretrievable situation of Armagh Cathedral. Several of the original fittings were returned to Enniscorthy and its original ceramic tiles restored but the installation of a victorian tantulus to serve as an ambury was, with hindsight, perhaps a little too iconic and its classical allusion all too poignant. The centrally sited sedilia gives the impression of nothing more than a modern carver. There are no choir stalls. Sheridan Tierney were architects for the 1996 restoration.

- November 20, 2005 at 12:08 am #767341

johannas

ParticipantDoes anyone know where one can obtain any published works on Ludwig Oppenheimer or of his firm. Thanks.

- November 20, 2005 at 12:19 am #767342

johannas

ParticipantHas anybody seen or mentioned Holy Trinity in Cork City

what a disaster. Fortunately St. Peter’s and Paul’s in Cork City seems to have escaped all vandalism so far! Has anybody pictures of Holy Trinity in Cork City before the vandals got in? - November 20, 2005 at 7:11 pm #767343

descamps

ParticipantAll you theorists should take a good look at the http://www.sacredarchitecture.org/pubs/saj/books/index.php

- November 20, 2005 at 7:46 pm #767344

Anonymous