Praxiteles

Forum Replies Created

- AuthorPosts

- February 19, 2010 at 10:00 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773684

Praxiteles

ParticipantSt Brendan’s Church, Birr, Co. Offaly

This pre-puginian Gothic church was begun in 1817. the site was donated by teh Earl of Rosse and the foundation stone laid by his son Viscount Oxmantown. The architect was Bernard Mullan.

February 18, 2010 at 10:10 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773683

February 18, 2010 at 10:10 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773683Praxiteles

ParticipantSt Brendan’s Church, Birr, Co. Offaly

Here is an interesting on on a window in Birr:

STAINED GLASS WINDOW UNVEILED IN IRELAND

Your browser does not support iframes.

February 18, 2010 at 3:37 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773681Praxiteles

ParticipantAnd here we have list of 100 top architecture blogs compiled by :Always Distinguish(ed).

ab ambiguitate ad claritatem.February 17, 2010 at 9:27 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773679Praxiteles

ParticipantAn article recently published in the Osservatore Romano by noted art historian Dr. Sandro Baragallo on the qualities to be sought in a new church:

A gloria sua e non per capriccio mio

di Sandro Barbagallo da L’Osservatore Romano 31.01.2010

Il Servizio nazionale italiano per l’edilizia di culto ha presentato in una mostra a Roma progetti di nuove chiese elaborati per un apposito concorso. La rassegna si tiene nella Sala 1 presso il convento dei padri passionisti alla Scala santa; e si tratta della quinta edizione di un concorso nazionale, indetto dalla Conferenza episcopale italiana (Cei), che in questi dieci anni ha esaminato centoundici progetti, suddivisi tra le diocesi di tutta Italia.

Come dice il responsabile dell’organismo della Cei monsignor Giuseppe Russo, “anche questa volta sono stati invitati a concorrere architetti che si sono distinti per capacità , esperienza e competenza nell’ambito della progettazione”.Ci si domanda quali dovrebbero essere le caratteristiche richieste alle nuove chiese. Prima fra tutte la riconoscibilità , poi una qualità formale, infine una buona qualità dell’impianto liturgico. Senza dimenticare naturalmente di proporre progetti ben inseriti nel contesto urbano. Fatte queste premesse, visitiamo la mostra.

Forse a causa di un allestimento che si avvale di uno spazio insufficiente, i progetti presentati alla Sala 1 si arrampicano sui muri, superando i due metri di altezza, per poi precipitare ad angolo retto sul pavimento. Si capirà come la lettura dei progetti, anche per i più esperti addetti ai lavori, diventi quasi indecifrabile. Avviene così che le architetture più complesse si confondano con quelle più banali e tutto l’insieme risulti di difficile interpretazione.

Bisogna ammettere che negli ultimi dieci anni la Chiesa italiana ha fatto uno sforzo di modernizzazione, dimostrando un coraggio fuori del comune nel bandire concorsi che l’avrebbero esposta a critiche a causa della forte visibilità . Ma se sbagliando si impara, forse basterebbe attenersi ad alcune regole generali.Per esempio ricordare che per secoli la Chiesa, intesa come spazio architettonico, è stata non solo un luogo di preghiera, ma anche di aggregazione, quindi con una funzione di “accoglienza”. Perché oggi, solo per l’ambizione di modernizzarsi, dovrebbe mostrarsi respingente?

Inoltre, perché in nome della modernità una chiesa non dovrebbe essere riconoscibile dall’esterno, come lo sono invece gli altri luoghi di culto in tutti i Paesi del mondo, dalla moschea al tempio buddista?

Perché dovremmo sostituire nel nostro immaginario collettivo di cattolici l’idea confortevole di “chiesa” con audaci architetture post-moderne senza nemmeno una croce a indicarne la “destinazione d’uso”?

Solo una piccola percentuale dei progetti presentati (come risulta dalla mostra di Roma) reca una croce sulla sommità . Tutti gli altri, a detta degli stessi architetti, contano sul particolare di alcune campane inserite a decorare la facciata oppure sull’effetto-sorpresa!In quanto poi all’intervento dell’artista all’interno, perché non ricordare gli egregi esempi del XX secolo che vanno da Matisse a Manzù, da Rouault a Greco? Artisti, questi, né accademici, né tradizionali. Come si può inserire in una chiesa la statua di una Madonna bifronte – da un lato caucasica e dall’altro africana – oppure una Trinità rappresentata da una madre e due figli piccoli, andando contro tutte le regole della tradizione e dell’iconografia cristiana? E vogliamo parlare dell’improbabile Cristo Risorto, mimetizzato in un ectoplasma giallo zolfo, da inserire sull’altare maggiore di una della chiese vincitrici del concorso?

Senza essere per principio contrari a una concezione non figurativa della rappresentazione artistica bisogna sottolineare che una cosa è la decorazione per la decorazione e un’altra l’arte sacra.

Quest’ultima deve obbedire alle regole iconografiche tradizionali e, pur rimanendo attuale, deve essere facilmente identificabile.

In quanto al liturgista, giustamente presente in ogni progetto, ci si chiede perché non gli si accordi più autorità in modo da indirizzare le velleità dell’architetto e degli artisti.Concludendo, la Chiesa ha dimostrato nel tempo di saper scegliere i propri artisti e di saper lasciare quindi traccia della propria grandezza e autorità . Questa responsabilità , egregiamente assolta nei secoli, continua oggi ad essere più importante che mai.

Per questa ragione bisogna forse diventare più cauti, scegliendo commissioni più severe ed esigenti, maggiormente preparate e attente alle necessità dei fedeli che, oggi più di ieri, hanno bisogno di essere incoraggiati a ritrovare le radici della propria appartenenza alla tradizione culturale e spirituale.

Ed è forse il caso di ricordare che in molte chiese, importanti per la ricchezza dei capolavori da esse contenuti, compare la scritta: Omne propter magnam gloriam suam. (“Tutto per la sua grande gloria”).February 17, 2010 at 8:07 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773678Praxiteles

ParticipantFrom the blog Always Distinguish(ed).

ab ambiguitate ad claritatem.A Christian Critique of Minimalism

Saturday, March 21st, 2009

This is going to be fairly straightforward, actually. I’d just like to draw your attention to a contrast. For those of you who read my post about John Pawson’s monastery of Our Lady of Novy Dvur and saw the clean, polished, magazine-quality photograph of the chapel that I posted (from the Novy Dvur website)—and especially for those of you who did not like it—you might appreciate this photograph that I found on Flickr, taken by Lorenzzo. For copyright reasons I can’t post it to the blog, but I recommend that you go see it and compare it to the one in this post (on the right).So, go check out the one on Flickr. You’ll see the chapel in a whole different light. And why do I call this a Christian critique of minimalism? Well, minimalism is almost like the newest kind of dualism. Consider the (in)famous motto of minimalism: “Less is more†attributed to Mies van der Rohe. The implication in architecture has a tendency to drive one to a puritan-like rigorism that produces buildings that only look good when they are not occupied and used by people. Consider even the magazine photo above: yes, it has the monks in it, but you might notice that conceptually the monks appear more as an extension of the space, an ornament to the furniture, than as the owners and users of the space. What I delight in about the photo on Flickr is that it shows you how the space is actually used. Suddenly you see benches that appear in front of the choir stalls, clearly not designed for the space, a couple of folding chairs, flowers in front of the altar, the appearance of a presider’s chair along with accompanying stools, and not the most flattering of daylighting.

The punchline to the minimalist enterprise, it seems to me, is that humans are not minimalists. We accumulate things, we get things dirty, we don’t all do the same things, we don’t all pray the same way, we don’t all look the same, we have bodies, for heaven’s sake! This is why I called minimalism almost a kind of dualism. There seems, to me, an underlying message that we must blot out the material world because it is uncontrollable. There’s another photo of the chapel at Novy Dvur that I have seen that lacks all the usual liturgical furniture you would expect in a monastery oratory: choir stalls, altar, ambo, tabernacle, etc… you only see the blank walls, the bare forms, the play of shadows and light. You lose all concept of scale (there are, of course, no humans in the picture) and it becomes a meaningless composition, perhaps pleasing to the eye. It is a strange worship of shadows.

Now, all of this is said in contrast to the ‘praises’ I sang of the monastery in the last post. I think there is something lovely about it, but it is the same thing that is lovely and romantic about a monk’s life to someone who is not a monk. That is to say, the contemplative life, though it may appear so to the observer, is not minimalist, it’s ascetic, and in this life the distance between the two is like the east from the west.February 17, 2010 at 8:06 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773677Praxiteles

ParticipantAn article on the monastery of Novy Dvur from the blog Always Distinguish(ed).

ab ambiguitate ad claritatem. :The Renewal of Religious Life and Architecture

Monday, March 16th, 2009

So, it’s been a while… again. But, here’s a bit of a subject that I have neglected for a bit. That is, until I discovered this gem on an architecture blog (I forget which one). The “gem†is English minimalist architect John Pawson’s (b. 1949) Cistercian Monastery of Novy Dvur in Bohemia in the Czech Republic—the monastery’s website can be seen here.

Give it a look see, but lest you complain that it is too austere or blank, remember that’s the way the Cistercians do it.

Be sure, also, if you are still intrigued after viewing the photos, to read Pawson’s essay about the design of the monastery. This, I think, tells you more about the design than the pictures will.

Now, to the main topic swimming around in your minds. Does he (meaning I, myself) like this?

Well, you knew, I hope, it wasn’t going to be that easy… (Never deny…)

With that said, I can hear the objections now to the picture I chose to show here: it looks like something from Star Trek, like some inter-galactic council about to meet. Where are the Christian symbols, for instance?

“Some of the vocabulary of Novy Dvur may be new – the cantilevered cloister, for instance, has no literal precedent in Cistercian architectural history – but my aim has been to remain true to the spirit of the twelfth century blueprint, to express the Cistercian spirit with absolute precision, in a language free from pastiche and charged with poetry.â€

The “Cistercian spirit†is not for everyone, nor is minimalism. But, as Pawson points out so concisely, in life as well as architecture, there is a beauty in simplicity that is unmatched by the crowding of superfluities and ornamentation. One could easily contrast the austerity of Pawson’s minimalism with the extravagance of the Baroque. One might also be tempted to choose between them, to say “I prefer†one to the other. One might also be led to believe that simplicity in design is really proof of a lack of imagination or skill. However, as many an architect will attest, and perhaps first among them Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, simple architectural details are often more difficult to realize than complicated ones. Why? Consider the complexities of construction, the delays, the inefficiency, the myriad professions on the jobsite that must be coordinated, the intricacies of accurate measurement, the difficulty of “getting it just right†and making things line up… for all the technology we have these days, making a truly straight line is still nearly impossible in construction. Further inspection into minimalist design reveals the real driving force behind the forms and materials: the play of light and space. This is of the essence of architecture—to create space and to illuminate it. In such an environment the tiniest of subtleties become massive design elements. The shape of a corner, the detail of how a wall meets the floor, all fill roles with which they are not commonly associated.

So, you might be saying “That’s great… you mean to tell me that these minimalist designs are actually the most complex and beautiful of them all, surpassing even the baroque in attention to detail? And, of course, all of this is lost on the lay observer.â€Ã‚ Well, to a certain extent, yes! I couldn’t appreciate the delicacy of Vivaldi’s Requiem Mass as well as some of my more musically inclined brothers can. Likewise, I wouldn’t expect them to immediately take delight in the simplicities of Pawson’s architecture.

What’s my personal verdict. Well, it is a critique as any architectural critique goes: Pawson is a master at minimalism, without a doubt, but he is also an architectural force to be reckoned with. Though one could not fully appreciate (or abhor) the full reality of the monastery at Novy Dvur without experiencing it in person, I believe it is safe to say from the material presented that Pawson exhibits a deft hand at design and with respect to the building as a monastery (aesthetics ‘aside’) has succeeded in creating a space well-proportioned to the life of a Christian monk. Is it beautiful? Without a doubt it expresses with clarity and precision the truths of monastic life and spirituality. Is it tasteful?  I don’t deny that I would have liked it to be clearer about what it is… but this is the language of symbols, something that architecture has struggled with for the past century. In that respect, I have some compassion for the design and Pawson, because I think that he has attempted to incorporate Christian symbolism in what is undeniably a very rigorist modern tendency to avoid what is classified as ‘pastiche’. Now, every architect might have his own notion of what consists of pastiche, but it is the contemporary problem par excellence in my opinion. The question is: how much can it look like the past without being unoriginal? It is the deadly flaw of modernism: the unswerving and uncompromising desire for originality.

And the subject line of the post? The Renewal of Religious Life? I thought it would be important to highlight that a project like this can’t come to pass without a few things in place first, most importantly, monks to live in the monastery. You look at the pictures and you notice quite a few young men. On the monastery website there are a few photos of what looks like a profession of vows or reception of the habit taking place in the chapter room (with the Patroness of the Americas and the unborn, Our Lady of Guadalupe, conspicuously watching over).

Pawson writes in his essay:

“The new Cistercian monastery of Novy Dvur is one of the less documented consequences of the fall of communism in former Czechoslovakia. For those with religious vocations the Velvet Revolution of 1989 brought not only political freedom, but the chance to travel abroad in pursuit of a contemplative way of life which no longer existed at home.â€

It seems that a particular Cistercian Abbey in Burgundy by the turn of the century (that is, 2000) had admitted a dozen or so monks from the Czech Republic after the fall of Communism. The wealth of vocations led the abbey to consider what one might call a “monastery plant†back in Bohemia.

The only way we will see a renewal of Catholic architecture is with a prior renewal of Catholic vocations (of all kinds, religious, sacerdotal, and familial). Only with a renewed and reformed Catholic culture will Catholic architecture be able to follow a still rather undetermined path towards a brighter, richer, more beautiful future.

February 16, 2010 at 7:39 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773676Praxiteles

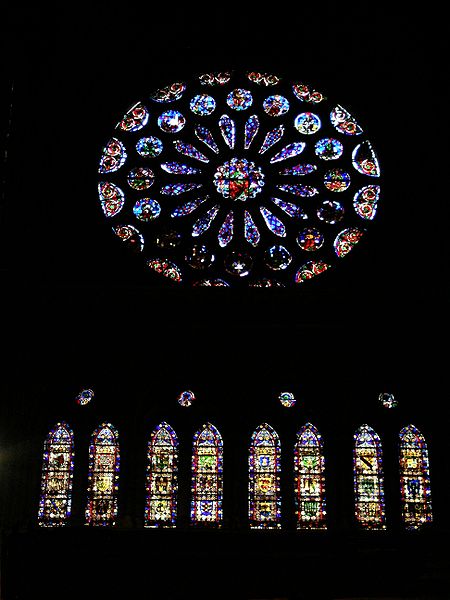

ParticipantLeon Cathedral

Some glass:

St Margaret and St Helena by Diego de Santillana:

February 16, 2010 at 7:34 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773675Praxiteles

ParticipantLeon Cathedral

General view of the nave looking towards the east:

February 16, 2010 at 7:31 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773674

February 16, 2010 at 7:31 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773674Praxiteles

ParticipantLeon Cathedral

The retablo of the High Altar:

February 15, 2010 at 11:11 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773673

February 15, 2010 at 11:11 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773673Praxiteles

ParticipantSome none too flattering comments on Leon cathedral from the Ecclesiologist of 1865:

February 15, 2010 at 11:06 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773672Praxiteles

ParticipantSome further information on Gothic architecture in Spain:

February 14, 2010 at 11:34 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773671Praxiteles

ParticipantLeon Cathedral

La actual catedral de León, iniciada en el siglo XIII, presenta un diseño del más depurado estilo gótico clásico francés. Conocida como la pulchra leonina1 y catedral de Santa MarÃa de Regla.

El cabildo temió un desenlace fatal, cuando el año 1857 comenzaron nuevamente a caer piedras de las bóvedas. Intervino entonces la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, y el gobierno encargó las obras a MatÃas Laviña. Éste se dispuso a desmontar la media naranja y los cuatro pináculos que la flanqueaban, pero el peligro de un total hundimiento se hacÃa más inminente. A su muerte se responsabilizó de las obras Hernández Callejo, quien pretendÃa seguir desmontando el edificio, cuando fue cesado en el cargo. Con los proyectos de Laviña, continuó la restauración Juan Madrazo el año 1869. Éste era un gran medievalista, buen conocedor del gótico francés. Modificó notablemente la disposición de las bóvedas, volvió a rehacer desde la arcada el hastial del sur y planificó todo el templo tal y como lo encontramos hoy. A Juan Madrazo le sucedió en el cargo Demetrio de los RÃos el año 1880. Purista, como el anterior, continuó dando a la catedral el aspecto primitivo, según su pensamiento racionalista, y desmontó el hastial occidental, que habÃa sido hecho por Juan López de Rojas y Juan de Badajoz el Mozo, en el siglo XVI. A su muerte fue nombrado arquitecto de la catedral Juan Bautista Lázaro, que concluyó los trabajos de restauración arquitectónica en la mayor parte del edificio, y el año 1895 emprendió la ardua tarea de recomponer las vidrieras. Estas llevaban varios años desmontadas y almacenadas, con grave deterioro. Fue ayudado por su colaborador, Juan Crisóstomo Torbado.

El 27 de mayo de 1966 un incendio arrasó toda la techumbre de las naves altas.

En las últimas décadas se está trabajando con gran intensidad en el refuerzo de las estructuras y suelos y el tratamiento de la piedra con las más novedosas técnicas, en un esfuerzo por conservar para la humanidad esta maravilla arquitectónicaFebruary 14, 2010 at 11:28 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773670Praxiteles

ParticipantLeon Cathedral

February 14, 2010 at 11:06 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773669Praxiteles

ParticipantLeon Cathedral

February 14, 2010 at 10:36 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773668Praxiteles

ParticipantLeon Cathedral

The tympan of the Portada de la Virgen Blanca

The detail shows the Last Judgment in the Tympanum of the main (west) door of the Cathedral.

In the Cathedral of León, the range of sculpture, from the second half of the thirteenth century, is even broader than at Burgos. The three doors of the west front with its portico, the transept doors, and the interior with its beautiful funerary monuments represent a cross-section of the plastic arts of the early Gothic. Clearly there were three principal sculptors, whose personalities are distinctly expressed. The foremost of the three, to whom the more important groups were entrusted, is none other than the man who carved the statues for the CoronerÃa Door in Burgos cathedral. His stone image of the Virgin and Child, known as the White Virgin (Virgen Blanca), is one of the finest sculptures ever made in Spain. The noble severity of his style stands opposed to the greater freedom and imagination of the second of the three sculptors of León, known only as the Master of the Last Judgment, whose narrative poetry is very personal and profoundly Spanish. The third master carved the apostles on the jambs of the south door and many statues in the main façade. The style of this artist is more restrained, closer to the manner of the French masters from Amiens who carved the Sarmental Door at Burgos.

February 14, 2010 at 10:34 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773667

February 14, 2010 at 10:34 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773667Praxiteles

ParticipantLeon Cathedral

The Portada de la Virgen Blanca (1250-1300)

Portada de la Virgen Blanca is the west portal of the Leon Cathedral. The west porch appears to be derived from Chartres; but the sculpture itself relates first to Burgos and then back to France (probably to Amiens and Reims).

February 14, 2010 at 10:14 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773666

February 14, 2010 at 10:14 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773666Praxiteles

ParticipantThe Cathedral of León is notable for its pure Gothic style, related to Rheims and Chartres. Its Gothic fabric has remained untouched and free of later additions and modifications. Its construction must have cost a tremendous effort, since León was not a wealthy diocese, particularly after it ceased to be the seat of the royal court. Only the determination of the prelate, Don Maretin Fernández, appointed in 1254, carried the project forward. The highest parts of the structure were not added until the fifteenth century. The richly carved west front contains three great doors, bneath a gable wall with rose windows, niches, and arcades. Designed as a Latin cross with very short arms, the interior of the cathedral, with its long chancel and chevet of five six-sided chapels, reflecs the same purity of style as its exterior. The many stained-glass windows and the height of the narrow nave contribute much to the general impression of airiness and light.

The Virgen Blanca (1250-1275)

The Virgen Blanca or Nuestra Señora la Blanca of the west portal of Leon Cathedral is the masterpiece of a certain Enrico, who died in 1277. He worked at Burgos and at Leon, and though he must have been trained at Amiens, he transformed the stylized grace of his masters’ 13th century French Gothic art into something more picturesque and anecdotal. The drapery folds are more broken, more angular, the Virgin is pleasant and kindly, and her Son, a lively and mischievous ‘niño’.

February 13, 2010 at 9:49 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773665

February 13, 2010 at 9:49 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773665Praxiteles

ParticipantLeon Cathedral

Some more glass

February 13, 2010 at 9:45 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773664

February 13, 2010 at 9:45 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773664Praxiteles

ParticipantLeon Cathedal

Doors:

February 13, 2010 at 9:42 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773663

February 13, 2010 at 9:42 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #773663Praxiteles

ParticipantRestoring monarchs and angels

BEATRIZ PORTINARI

11 December 2007

El Pais – English EditionTeam works to return stained glass of León Cathedral to its former glory

More than a century after the last restoration of the stained glass windows of León Cathedral, a group of experts went back up its spiral staircase, crept past gothic arches, and clambered onto a scaffolding 26 meters above the ground. Their task was to undertake the biggest restoration in the entire history of the building. The most impressive glass windows in all of Spain had been so badly damaged by corrosion and dirt that the light barely filtered through anymore. Now, specialized craftsmen have until 2009 to clean 450 square meters of glass – out of a staggering total of 1,800 square meters – and recover the biblical messages depicted in each window.

“It is a work of restoration, but above all one of preventative conservation,” explains José Manuel RodrÃguez, who is coordinating the €4.5-million project. “The deterioration was due to corrosive agents in the air, microorganisms, rain, pollution, even vandalism […] So we are trying to prevent any of that from happening again.”

In the 1990s, somebody threw stones at these priceless windows and shattered several panes. That is why there is now a double protection system in place consisting of mesh wire and a transparent glass pane that creates an insulated chamber to prevent damage from condensation.

But conservationists have very little room for maneuver this time round, warns RodrÃguez. “All we’re doing now is cleaning and restoring what is already there, not like in the 19th century, the last time the windows were restored. We believe that back then the restorers even added a few panes in what were previously empty spaces.”

Fortunately, those master craftsmen who saved the cathedral in 1895 were fans of the designs of the Middle Ages and they respected the original French Gothic style, in imitation of the cathedrals of Reims and Amiens in France. The predominant colors – blue, red, yellow and green – continued to deck the tunics of the monarchs, prophets, apostles and angels that featured on the original medieval windows.

The challenge now is to do as well, or even better than, those 19th century restorers. After carefully studying the techniques and materials used in the 13th and 14th centuries, the craftsmen and women now at work on the building have submerged themselves in a world of dust, rust, lead, paintbrushes and scalpels to bring back to life the old pictures depicting the main stories of Christianity for the benefit of what was a mainly illiterate population. From east to south, the rays of the sun light up the windows, but the northern side of the cathedral, which depicts passages of the Old Testament, is always in the dark – because Christ had not yet illuminated the world with his presence.

“This window is in such a bad state that after cleaning it the change in colors is going to be spectacular,” says Arantxa Revuelta, one of the restorers, in reference to a 13th-century pane depicting the Tree of Jesse.

- AuthorPosts