Praxiteles

Forum Replies Created

- AuthorPosts

- February 15, 2011 at 9:35 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #774511

Praxiteles

ParticipantAnd the article from L’Osservatore Romano published by Maria Antonietta Crippa

La croce forma e sostanza delle planimetrie delle antiche basiliche

“Con la consapevolezza di essere un solo corpo”.

Da “L’Osservatore Romano” del 9 febbraio 2011. Testo a sua volta ripreso dal volume di più autori: “Gesù. Il corpo, il volto nell’arte”, Silvana Editoriale, Milano, 2010di Maria Antonietta Crippa

Nei preziosi testi nei quali Edgar de Bruyne si impegnò a esplorare la mentalità medievale per catturarne” l’âme et ses créations du point de vue de ses propres ideaux”, si trovano pagine che invitano a ritenere molto importante la connessione, lungo tutto il medioevo, tra forma basilicale planimetrica a croce latina e figura di Cristo crocifisso.

Vi si legge, a esempio, che le corrispondenze tra “le proporzioni del corpo umano e quelle dell’edificio” si basavano, in primo luogo, sulla dottrina architettonica dei numeri; che in questa dottrina due erano le figure principali, il quadrato e il cerchio, nei quali veniva inscritto l’uomo; che, tra i molti autori che collegavano basilica cristiana, corpo umano e corpo di Cristo crocifisso, un vescovo del XIII secolo, Durando di Mende, nel suo “Rationale” ha affermato che la chiesa è figura di un uomo sdraiato con le braccia stese a croce.

Commenta de Bruyne: “Ora, ogni chiesa in pietra è fatta ad immagine di Cristo, pur essendo anche simbolo della Chiesa spirituale che è il suo corpo mistico. Qui si ritrovano ancora le idee dell’Antichità. Vitruvio ci insegna che tra le proporzioni del corpo umano e quelle del tempio vi è una certa analogia… I templi sono rotondi o rettangolari e le loro proporzioni sono derivate sia dall’uomo circolare sia dall’uomo quadrato. Per questo, secondo Onorio d’Autun, le chiese cristiane provengono da due tipi principali: esse hanno forma di croce, per mostrare che il popolo cristiano è crocifisso al mondo, oppure di cerchio per simbolizzare l’Eternità senza fine fondata sulla carità”.

Se de Bruyne, analizzando i sistemi filosofici e teologici del medioevo, si stupiva per l’imponente evidenza di una “immensa contemplazione del Bello a carattere artistico”, in anni a noi più vicini Henri de Lubac ha sottolineato invece la “forte volontà costruttiva” del medioevo. La metafora dell’edificio ebbe allora posizione privilegiata nella letteratura dottrinale e spirituale; ad esempio: “Dio – afferma sant’Odilone – è ‘creator et renovator totius machinae mundi’… Il corpo di Cristo, spiega Ruperto, è la casa nella quale abita la pienezza della divinità… la croce di Cristo è una machina, che Cristo stesso ha voluto costruire al fine di restaurare e riunire tutte le cose”.

La costruzione principale a cui si faceva sempre riferimento in tutte le “costruzioni spirituali” filosofiche e teologiche, era quella della Chiesa come corpo di Cristo, “universa spiritualis fabricae” struttura, arca di Noè, tabernacolo, tempio, casa delle nozze, Gerusalemme celeste, città dell’Apocalisse, costruzione di cui è artefice Cristo “idem ipse fundator et fundamentum”. In essa: “La croce costituisce l’armatura interna che terrà unito tutto l’insieme”; inoltre: “Di quella grande Chiesa, la chiesa visibile e materiale è il segno, e ogni cerimonia della sua dedicazione simboleggia un aspetto dell’opera che deve essere compiuta in ciascuno di noi, affinché diventiamo tutti insieme la dimora definitiva della Divinità”.

È certamente suggestivo, e non casuale, che Ugo di San Vittore invitasse alla costruzione dell’autocoscienza cristiana evocandone la stretta analogia con l’organizzazione di un cantiere edilizio, a sua volta analogo alla costruzione del cosmo: “Tutto è stato fatto con ordine; procedi ordinatamente. Dunque, accingendoti a fabbricare, dapprima metti il fondamento della storia; poi, mediante il significato tipico, innalza la costruzione della mente sopra la rocca della fede; infine mediante la piacevolezza della moralità, dipingi l’edificio sovrapponendo per così dire un bellissimo colore”.

Non è possibile, nel grande repertorio di forme basilicali dal tardo antico in poi, sintetizzare in poche righe ragioni e modi dei processi evolutivi, delle filiazioni formali e costruttive dei complessi basilicali; in particolare, nel cercare le ragioni del passaggio dalla prima fase sperimentale al romanico, gli studiosi si trovano a doversi accontentare di “stabilire le analogie tra la basilica protocristiana e quella romanica”.

Scorrendo velocemente la storia dell’architettura è, tuttavia, sorprendente trovare una costanza planimetrica a croce latina – dal preromanico, al romanico maturo, al gotico soprattutto, ma anche oltre – costanza tipologica che apparenta situazioni storiche ed edilizie, stilistico-costruttive e di sintesi formali, tra loro molto diverse. Essendo essa prevalente e non intermittente, segnala una predilezione profondamente radicata nel sentire ecclesiastico e collettivo, di cui ancora non si è trovata la trama strutturante.

Solo a titolo esemplificativo richiamo due casi quasi coevi: la cattedrale di Chartres, ricostruita sulle ceneri della precedente costruzione romanica tra 1194 e 1230 circa, e la basilica di San Francesco ad Assisi, iniziata nel 1228 e consacrata nel 1253.

La planimetria della prima, momento vertice del gotico francese, è ben difficilmente paragonabile a quella, per chiesa a due piani, della seconda, ritenuta poderoso avvio della storia dell’arte gotica in Italia. Ambedue, tuttavia, non sono che varianti della planimetria a croce latina.

In pieno rinascimento, nel suo trattato di architettura del 1554, il senese Pietro Cataneo ripropose esplicitamente la stretta connessione tra pianta a croce latina e corpo di Cristo crocifisso, facendo perno, come tutti i trattatisti da Leon Battista Alberti fino a Palladio e a Serlio, sull’autorità di Vitruvio, in particolare sul tema, esaminato nel terzo libro dell’architetto romano, dell’iscrizione del corpo umano nel quadrato e nel cerchio.

Ma mentre la gran parte dei trattatisti rinascimentali predilesse lo schema “ad circulum”, connesso all’interpretazione della simmetria come commensurabilità delle singole parti fra loro e con l’intero corpo edilizio, Cataneo preferì recuperare da Vitruvio la matrice “ad quadratura”, che gli consentiva di elaborare una tipologia di croce latina marcatamente longitudinale.

Essa gli permetteva anche la rigorosa inscrivibilità, nella planimetria della chiesa, della figura di Cristo crocifisso, indispensabile poiché: “considerato dunque che per mezzo della croce piacque a Dio di darci il regno del cielo, si deve per noi fedeli… grandemente venerarla, massime nell’edificare il principale tempio o chiesa chatedrale della città, dedicando quella a Gesù Cristo crocifisso, dal suo santissimo corpo pigliare le misure del tempio, lassando in luogo della sua divina testa il vano per il cappellone nel quale i preti stanno a celebrare il culto suo, in luogo del suo di ogni ben largo petto sia lassato il vano per la principal tribuna, dal quale si muovino braccia, nella sommità delle quali, in luogo delle sue liberalissime mani, una entrata per banda si potrà fare, in luogo dei suoi sempre di carità vivaci piedi una, o tre, over cinque entrate secondo le navate capacità si lassino”.

Ai principi contenuti nel trattato di Cataneo è stato riconosciuto il valore di “virata di importanza storica” in quanto primo avvio dell’orientamento cui si collegano sia molte idee contenute nel trattato di san Carlo Borromeo “Instructiones fabricae et supellectilis ecclesiasticae” del 1577, sia la decisione del prolungamento maderniano della basilica a pianta centrale di San Pietro in Vaticano, di Michelangelo.

__________

> L’Osservatore Romano”

February 15, 2011 at 9:29 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #774510Praxiteles

ParticipantThe article published in L’Osservatore Romano by Timothy Verdon, priest of the archdiocese of Florence and well known art-critic:

BASILICA AND CIRCLE. THE TRADITION OF THE GREAT CHURCHES OF ROME

by Timothy Verdon

One of the distinctive characteristics of Western Christianity is the desire to build great churches: still today, in a Europe that does not want to recognize its Christian roots officially, the most imposing historical buildings of the cities are cathedrals, monastic churches, or shrines. How did this tradition emerge?

The Christian idea of the place of worship underwent a first fundamental transformation in Italy, and specifically in Rome, beginning at the time of Constantine.

Previously, as we learn from the letters of Saint Paul, in Rome and in other evangelized cities the Church was structured in small communities identifiable on the basis of the private homes in which the members gathered. In his letter to the Romans, for example, greeting his friends Aquila and Priscilla, Paul also greeted “the community that meets in their home” (Romans 16:3-5).

But the homes used in Rome in the 1st century also included the patrician “domus” and perhaps even the imperial “palatium”: writing from Rome to the believers of Philippi between the years 61 and 63, Saint Paul would say: “All the holy ones send you their greetings, especially those of Caesar’s household” (Philippians 4:22).

With the conversion to the new faith on the part of the highest ranks of society between the end of the 3rd and the beginning of the 4th century, some of the “homes” that were permanently dedicated to the service of the “ecclesia” were grand and luxurious: these included an audience hall of the residence of the mother empress Helena, the Palazzo Sessoriano, which later became the basilica of The Holy Cross in Jerusalem.

It would be above all Helena’s son, the emperor Constantine, who would give official dignity to this tendency, exalting the new faith through the construction of a real and proper network of great churches on the architectural model of the public halls or royal residences of the empire: the basilicas.

Just as for three hundred years the Christian communities had celebrated their rites in ordinary rooms, in private homes and in the “insulae” of the Greco-Roman cities, without feeling a particular need to distinguish their places of worship from the world around them, so also, even after the Church’s rise through society, the grandiose structures built by the imperial government were inserted into the existing architectural fabric of the cities in which they found themselves.

The Constantinian foundations and those of the 5th century were many, and very large: Saint John Lateran, possibly begun as early as 312-13, was of titanic dimensions: 98 by 56 meters; the cemetery basilica of Saint Sebastian, on the Appian Way, was 75 meters long; the original basilica of Saint Lawrence on the Via Tiburtina was 98 meters long.

There was a basilica on the Via Labicana, next to the “martirion” of saints Marcellinus and Peter, containing the mausoleum of the empress Helena, and there was another on the Via Nomentana, near the memorial of Saint Agnes, where Constantine’s daughter, Costanza, had had her mausoleum built, the present-day church of Saint Costanza.

Above all, the ancient basilica of Saint Peter was colossal, with a facade about 64 meters wide and a portico 12 meters deep. The naves, excluding the sanctuary, were 90 meters long, and the central one was 23.5 meters wide, with a height of 32.5, while the lateral aisles were respectively 18 and 14.8 meters high.

In the setting of the imperial court, a step was then taken that was full of significance for the history of Christian architecture: the adaptation for liturgical purposes of the circular or cylindrical building typical of the mausoleums of illustrious figures in late antiquity.

For the Greco-Roman sensibility, in fact, the cylindrical-closed form suggested the mystery of death; precisely this configuration had been used in the 4th century in Jerusalem for the Constantinian structure of the “Anastasis,” containing the empty tomb of Christ. The same form was then used by Constantine’s daughter for her own mausoleum on the Via Nomentana, next to the ancient cemetery basilica of Saint Agnes.

Such circular structures have a particular symbolism. While the more common longitudinal basilicas imply a journey – from the entrance to the altar – the circular form, without beginning and without end, speaks of the infinite: arriving at its center connotes the end of the search, the arrival at the greatly desired port.

At the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, where one first passed through a longitudinal basilica to then – across a courtyard – enter the circular structure, the overall spatial experience was almost a metaphor of search and discovery: of the journey of faith and of the certitude with which God puts an end to man’s searching, admitting him into the infinite light.

In the 5th century, the largest Roman church with central symmetry, Saint Stephen in the Round, would propose a new experience. The longitudinal basilica becomes an immense rectangular courtyard around the circular element, which in turn becomes a concentric labyrinth with multiple entrances. From the chapels one then passes into the penultimate ring, higher and more luminous than the outer ones, which finally gives access to the highest cylindrical central space, a well of light in the heart of the building.

This means that at Saint Stephen in the Round, the meaning of the Christian journey was articulated in terms of mystagogy, of initiation into the mystery: no longer as a linear movement, nor as a simple arrival, but in the experience of a penetration by degrees: from the outside toward the center, from the shadows toward the light, this perhaps being a metaphor for the life of a Church that had found the reason for its communion not only in the historical roots of a shared “romanitas,” but also in the convergence toward Him who is the light of men.

It is evocative, in fact, to place the circular plan of this church beside a contemporaneous image of Christ who ascends in the circular “clipeus” symbolizing the light, in one of the wooden panels of the doors of the basilica of Saint Sabina, on the Aventine hill.

It is the Christ of Revelation, the Alpha and the Omega of human history, presented among the symbols of the four evangelists, with – below him – saints Peter and Paul, who are lifting a wreath onto the head of a woman. She, with her arms raised in prayer, symbolizes the Church herself, who yearns for her Bridegroom.

In Rome, for the first time, the Church is identified by extension with Him who, immolated, is now “worthy to receive power and riches, wisdom and strength, honor and glory and blessing” (Revelation 5:12). It spontaneously occupied, transforming them, the architectural and conceptual spaces of the ancient empire, convinced that God, in addition to manifesting himself in the moral greatness of Israel, had also manifested himself in the material splendor of Rome. The marble magnificence of the once pagan city was interpreted as a foreshadowing of the city of Revelation, the heavenly Jerusalem whose walls will be covered with rare and precious stones.

Rome is, in fact, the city of the Apocalypse – of the unveiling of the hidden meaning of history – and from the 5th century onward, the messages communicated in the iconographic layout of the most important Roman churches have been “apocalyptic.”

Christ dressed in the golden toga as “Dominus dominantium,” Lord of lords, seated on the throne or standing with the inscription of his divine power in hand and, in front of him, the twenty-four elders who worship him day and night, wafting incense that symbolizes the prayers of the saints: these are the images realized in the sanctuaries of the great new basilicas.

In a number of these churches, moreover, the scenes revelatory of eternity completed grandiose historical cycles on the side walls, with episodes from the Old and New Testament, thus insisting on heavenly glory as the resolution of earthly events.

At Saint Peter’s on the Vatican hill, this message was already anticipated on the outside, with a monumental mosaic that covered the upper part of the facade of the basilica (drawn in an 11th century codex originally from Farfa and now kept at Eton College near Windsor), placing before the eyes of faithful and pilgrims the Lamb, the elders, and the countless multitude of those who stand “before the throne and before the Lamb, wearing white robes” (Revelation 7:9).

This characteristic of life in the ancient capital, the multitude, would also take on apocalyptic connotations in Christian Rome. The city whose theaters and amphiteaters had received immense crowds would become the papal Rome that regularly receives men and women “of every nation, race, people, and tongue” (Revelation 7:9). This phenomenon explains the creation – first at the Lateran, and then at the Vatican – of spaces sufficient for the crowds of pilgrims from all over the world, spaces that express continuity with the ancient empire: Saint Peter’s basilica and the square in front of it, in fact, stand on the site of a circus built in the 1st century by the emperors Caligula and Nero.

The gigantic theaters and amphitheaters of the City, which still today testify to the empire’s capacity to channel oceanic crowds toward one point, are part of the experience of the primitive Church of Rome. Even if the converts to the new faith must not have been assiduous patrons of the theater and the circus, they certainly could not have ignored the attraction that such places exercised on their contemporaries.

This means that not only the idea of magnificent spaces of collective life, but also that of spectacle – of gatherings to see together events that create unity through the emotion shared by hundreds of thousands of people – were part of the cultural and human climate of the primitive Roman Church.

__________________

The article by Timothy Verdon reproduced above was published in “L’Osservatore Romano” of February 10, 2011, with the title: “La tradizione europea delle grandi chiese. Dagli angoli della vita al cerchio dell’eternità”:

> L’Osservatore Romano

February 15, 2011 at 9:24 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #774509Praxiteles

ParticipantFinally, we appear to be getting somewhere.

From http://chiesa.espresso.repubblica.it/?eng=y

New Churches. The Vatican Flunks the Italian Bishops

In “L’Osservatore Romano,” Cardinal Ravasi and the “superstar” Paolo Portoghesi criticize the new sacred buildings constructed in Italy with the sponsorship of the episcopal conference. Why they break with tradition and deform the liturgy. A commentary by Timothy Verdon

by Sandro Magiser

ROME, February 14, 2011 – The three images juxtaposed above depict a detail of the wooden door of the Roman basilica of Saint Sabina, from the 5th century; the interior of the church of Saint Stephen in the Round in Rome, also from the 5th century; and the design of a church inaugurated in Milan in 1981, the parish of God the Father.

The question must be asked: are modern buildings like the third one depicted above in continuity or in rupture with the architectural, liturgical, and theological tradition of the Church?

Various modern churches are constructed in the form of a circle. Just as it is the circle that characterizes the two ancient examples of sacred art reproduced above. But is this enough to guarantee continuity with tradition?

Or are aesthetic criteria sufficient to judge the quality of a new church?

At this start of the new year, a controversy over this has exploded in Rome and Italy. And not only among the specialists. The newspaper of the Holy See, “L’Osservatore Romano,” has entered the fray, and on several occasions has severely criticized some of the most famous examples of new sacred architecture sponsored by the Italian episcopate.

*

It was started by Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi, president of the pontifical council for culture, with a “lectio magistralis” at the architecture faculty of the University of Rome “La Sapienza,” reproduced in its entirety in the January 17-18 issue of the Vatican newspaper.

Ravasi came out swinging against those modern churches “in which we find ourselves lost as in a conference hall, distracted as in a sports arena, packed in as at a tennis court, degraded as in a pretentious and vulgar house.”

No names. But on January 20, again in “L’Osservatore Romano,” the architect Paolo Portoghesi took direct aim at the three churches that had won the national contest announced by the Italian episcopal conference in 2000, built in Foligno by Massimiliano Fuksas, in Catanzaro by Alessandro Pizzolato, and in Modena by Mauro Galantino.

Portoghesi is himself a world-famous “superstar”: the Grand Mosque of Rome is one of his designs. For some time he has criticized some of the new churches built by trendy architects and praised by the hierarchy. The most famous and talked about of these include the church built by Renzo Piano in San Giovanni Rotondo, over the tomb of Padre Pio, and the one built by Richard Meier in the Roman neighborhood of Tor Tre Teste.

This time, in “L’Osservatore Romano,” Portoghesi mainly goes after the church of Jesus the Redeemer in Modena, designed by Galantino. He acknowledges its aesthetic virtues, its harmony of form, its conceptual cleanness. He also acknowledges the architect’s intention to “give more dynamism to the liturgical event.”

But then he asks: “Where are the sacred signs that make a church recognizable?” On the outside – he observes – there are none, except for the bells, “which, however, could also be found in a city hall.” While on the inside, “the iconological role is assigned to a ‘garden of olives’ set up in a little enclosure behind the altar, and to the ‘waters of the Jordan’ reduced to a little trough of standing water hemmed in between two walls and ending at the baptistry.”

But the worst, in Portoghesi’s view, appears during the celebration of the Mass:

“The community of the faithful is divided into two sections facing each other, and in the middle a big empty space with the altar and the ambo at opposite ends. The two sections facing each other and the wandering of the celebrants between the two ends threaten not only the traditional unity of the praying community, but also what was the great achievement of Vatican Council II, the image of the assembly as the people of God on its journey. Why look at each other? Why not look together toward the fundamental places of the liturgy and the image of Christ? Why are the places of the liturgy, the altar and the ambo, on opposite ends instead of being together? Trapped in the pews, divided into sectors like the cohorts of an army, the faithful are forced, while remaining immobile, to turn their heads to the right, then to the left. The figure of the Crucifix is placed on the side of the altar, in correspondence with the section on the left, with the inevitable result that many of the faithful cannot see it without craning their necks.”

Portoghesi quotes Benedict XVI, and then continues:

“It is to be hoped that these timely statements from the chair of Saint Peter will make liturgists and architects understand that re-evangelization also passes through the churches with a small ‘c’, and indeed requires the creative effort of innovation, but also an attentive consideration of tradition, which has always been not mere conservation, but the handing down of a heritage to be brought to fruition.”

And he concludes:

“The new church of Modena is a glaring demonstration of the fact that the aesthetic quality of the architecture is not enough to make a space a true church, a place in which the faithful may be helped to feel like living stones of a temple of which Christ is the cornerstone.”

*

These criticisms were answered, in “Corriere della Sera” on February 8, by the architect Galantino and Bishop Ernesto Mandara, responsible for new churches in the diocese of Rome.

Galantino defended his architectural decisions, maintaining that he wanted to arrange the faithful “as around a table, conceptually reconstructing the last supper.” And he recalled that he had developed his reflections in the 1980’s in Milan, with Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini.

(An aside. The Milanese church in the illustration at the top of this page is one of the products of that climate. Planned by the architects Giancarlo Ragazzi and Giuseppe Marvelli, it was expressly conceived as “a place of encounter and prayer for the believers of all religions,” devoid of specific signs both on the outside and on the inside. Movable walls can divide the interior into three compartments: the middle one for Catholic rites, and the two sides intended for Jews and Muslims. The current pastor is laboriously restoring the church to entirely Catholic use, with two crosses on the outside, with stained glass and Christian images on the inside, and with a large Christ on the cross above the altar.)

Bishop Mandara also defended his actions and those of the Italian episcopal conference:

“Probably if we look at the past we find examples of unsuccessful buildings that lend support to Cardinal Ravasi, but I am deeply satisfied with the results of recent years. The churches that have been built express very well both the sense of the sacred and that of hospitality.”

On February 9, “L’Osservatore Romano” reported both of the statements of Galantino and Mandara. But it also gave another opportunity to Portoghesi, who said:

“After the Council, there were many attempts to leap forward, in various directions. The church has lost its specificity, it has become a building like the others. But recognizability is a fundamental reality, a stage of that re-Christianization of the West of which the pope speaks. As for the orientation of liturgical prayer, the people of God on its journey toward salvation cannot be static, it moves in a direction; the ideal would be to orient the church to the east, where the sun rises. We must not be afraid of that modernity which the Church itself has contributed to creating, every generation has the duty of reinterpreting the content of the past, but considering tradition as an element of strength to draw upon.”

Not only that. On February 9 and the following day, “L’Osservatore Romano” returned to the issue with two erudite contributions from two experts, both intended to demonstrate the distinctive characteristics of the traditional architecture of Christian churches.

*

The first of the two statements is by Maria Antonietta Crippa, a professor of architecture at the Policlinico di Milano.

It shows how the preeminence given by Christian architecture to churches in the form of a Latin cross is inspired both by the classical period (Vitruvius, with the analogy between the proportions of the body and of the temple) and above all by the vision of the Church as the body of Christ, and of Christ crucified.

But together with the square, the circle also has a place in this architectural tradition. According to the medieval authors, the Christian churches “have the form of a cross to show that the Christian people are crucified to the world; or of a circle to symbolize eternity.”

Or even of a cross and a circle at the same time. As happened in the 16th century with the prolongation of the nave of the new basilica of Saint Peter, originally with central symmetry in Michelangelo’s design.

*

The second and even more important contribution, in “L’Osservatore Romano” on February 10, is from Timothy Verdon, an American art historian and priest, a professor at Princeton and director of the office for sacred art of the archdiocese of Florence.

His article is reproduced in its entirety below. And it shows how the first great churches in Rome were built, in the 4th century, precisely by adapting for Christian use two models of classical architecture: the longitudinal one of the basilica and the circular one, with central symmetry.

In Jerusalem, the church of the Holy Sepulcher built by the emperor Constantine combines both models. But also in Rome, the first great church with central symmetry, that of Saint Stephen in the Round from the 5th century – the interior of which can be seen in the illustration at the top of this page – rises from a huge rectangular courtyard.

In any case, the churches with central symmetry are not devoid of decoration, much less do they make the assembly of the faithful fold back on itself. The faithful enter them as on a path of initiation, up to the column of light that is at the center of the building and is Christ “lux mundi.”

That Christ who in the contemporaneous door of Saint Sabina – see the illustration – appears at the center of the celestial circle and receives the “oriented” prayer of the woman below him, the Church crowned as his bride.

This is the great architectural, liturgical, and theological tradition of the Christian churches. Of yesterday, today, and forever.

February 14, 2011 at 10:45 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #774508Praxiteles

ParticipantIt sounds very much as though Vosko’s wreckovation manual is being deployed here in a thorough outpouring of dated Enlightment perceptions on the part of the “conoscenti” of what is or is not best for the ignorant and liturgically challenged.

February 9, 2011 at 5:43 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #774505Praxiteles

ParticipantPraxiteles has just received the following press release:

[align=]St. Colman’s Society for Catholic Liturgy[/align]

__________Press release

Benedict XVI and Beauty in Sacred Art and Architecture

Proceedings of the Second Fota International Liturgy ConferenceSt. Colman’s Society for Catholic Liturgy is pleased to announce the publication of Benedict XVI and Beauty in Sacred Art and Architecture: Proceedings of the Second Fota International Liturgy Conference by Four Courts Press, Dublin, Ireland on 25 March 2011.

The book is edited by D. Vincent Twomey and Janet Rutherford.

In an historic meeting with artists in 2009, Pope Benedict XVI summoned the Church and the world to engage in ‘an authentic “renaissance” of art’. The Second Fota International Liturgy Conference was convened the same year to examine just how to do so. Architecture, painting, sculpture, furnishings – all have an indispensible role to play in raising our hearts and minds to God. Developing the themes set out in Benedict XVI and the Sacred Liturgy, this second volume in the series examines the fundamental principles that guide the Church in determining which works of art are truly ‘signs and symbols of the supernatural world’ (Sacrosanctum concilium 122). Pope Benedict XVI’s extraordinary combination of theological depth and cultural breadth makes him one of the most important voices in this discussion. The essays contained here draw on the richness of the Pontiff’s thought to suggest how the Church might overcome the ‘new iconoclasm’ of the post-Conciliar period in order to contemplate the face of Christ more clearly. The authors address questions both practical and theoretical, and their proposals are as commonsensical as they are bold. Benedict XVI and Beauty in Sacred Art and Architecture promises to sharpen our Christian understanding of beauty, and to inspire the elevation of liturgical art from the mundane to the celestial – from the banal to the sublime.

The best current offer on the book is available at the Book Depository and may be pre-ordered online at https://www.bookdepository.com/book/9781846823091/Benedict-XVI-and-Beauty-in-Sacred-Art-andBibliographical details:

Physical properties

Format: Hardback

Number of pages: 224

Width: 156.00 mm

Height: 234.00 mm

Illustrations note

illustrations

ISBN

ISBN 13: 9781846823091

ISBN 10: 1846823099February 8, 2011 at 2:35 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #774506Praxiteles

ParticipantCashel works essential – Manseragh

The Minister for Public Works Dr Martin Mansergh has said that the maintenance work currently taking place at one of Ireland’s most famous ecclesiastical sites is essential.

Dr Mansergh , who is also a TD for South Tipperary, said that the work currently taking place at Saint Cormac’s Chapel in the Rock of Cashel is essential.

He said that if the work does not take place, “There is a risk of what has happened in Pompeii recently, where a historic structure collapsed happening in Ireland.”

Mr Mansergh was responding to queries concerning the length of time that scaffolding will be in place as based on previous experience, the scaffolding can often remain in place for up to 12 years even though the entire building was built in just eight years.

According to Minister Mansergh, “The temporary roof with access scaffolding now in place will allow the building to dry out and facilitate conservation and repair work to its sandstone fabric and help the long-term conservation of the wall paintings.”

He added, “The presence of scaffolding advertises the fact that conservation works are taking place. Stirling Castle and Roslyn Chapel in Scotland seem to have perpetual covered scaffolding, while scaffolding is always in evidence in Hampton Court, Westminster Abbey and the Tower of London.”

While most of the buildings that now survive in the Rock of Cashel date from the 12th and 13th century’s it is also thought that it was also the site where the King of Munster was baptised by Saint Patrick in the 5th century.

February 8, 2011 at 2:33 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #774504Praxiteles

ParticipantCashel works essential – Manseragh

The Minister for Public Works Dr Martin Mansergh has said that the maintenance work currently taking place at one of Ireland’s most famous ecclesiastical sites is essential.

Dr Mansergh , who is also a TD for South Tipperary, said that the work currently taking place at Saint Cormac’s Chapel in the Rock of Cashel is essential.

He said that if the work does not take place, “There is a risk of what has happened in Pompeii recently, where a historic structure collapsed happening in Ireland.”

Mr Mansergh was responding to queries concerning the length of time that scaffolding will be in place as based on previous experience, the scaffolding can often remain in place for up to 12 years even though the entire building was built in just eight years.

According to Minister Mansergh, “The temporary roof with access scaffolding now in place will allow the building to dry out and facilitate conservation and repair work to its sandstone fabric and help the long-term conservation of the wall paintings.”

He added, “The presence of scaffolding advertises the fact that conservation works are taking place. Stirling Castle and Roslyn Chapel in Scotland seem to have perpetual covered scaffolding, while scaffolding is always in evidence in Hampton Court, Westminster Abbey and the Tower of London.”

While most of the buildings that now survive in the Rock of Cashel date from the 12th and 13th century’s it is also thought that it was also the site where the King of Munster was baptised by Saint Patrick in the 5th century.

February 6, 2011 at 8:16 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #774503Praxiteles

ParticipantInteresting that Mr Hurler thinks that he is building a flag-ship. We propose some reflections for him:

“Courage!” he said, and pointed toward the land,

“This mounting wave will roll us shoreward soon.”

In the afternoon they came unto a land

In which it seemed always afternoon.

All round the coast the languid air did swoon,

Breathing like one that hath a weary dream.

Full-faced above the valley stood the moon;

And like a downward smoke, the slender stream

Along the cliff to fall and pause and fall did seem.A land of streams! some, like a downward smoke,

Slow-dropping veils of thinnest lawn, did go;

And some thro’ wavering lights and shadows broke,

Rolling a slumbrous sheet of foam below.

They saw the gleaming river seaward flow

From the inner land: far off, three mountain-tops,

Three silent pinnacles of aged snow,

Stood sunset-flush’d: and, dew’d with showery drops,

Up-clomb the shadowy pine above the woven copse.The charmed sunset linger’d low adown

In the red West: thro’ mountain clefts the dale

Was seen far inland, and the yellow down

Border’d with palm, and many a winding vale

And meadow, set with slender galingale;

A land where all things always seem’d the same!

And round about the keel with faces pale,

Dark faces pale against that rosy flame,

The mild-eyed melancholy Lotos-eaters came.Branches they bore of that enchanted stem,

Laden with flower and fruit, whereof they gave

To each, but whoso did receive of them,

And taste, to him the gushing of the wave

Far far away did seem to mourn and rave

On alien shores; and if his fellow spake,

His voice was thin, as voices from the grave;

And deep-asleep he seem’d, yet all awake,

And music in his ears his beating heart did make.They sat them down upon the yellow sand,

Between the sun and moon upon the shore;

And sweet it was to dream of Fatherland,

Of child, and wife, and slave; but evermore

Most weary seem’d the sea, weary the oar,

Weary the wandering fields of barren foam.

Then some one said, “We will return no more”;

And all at once they sang, “Our island home

Is far beyond the wave; we will no longer roam.”Choric Song

I

There is sweet music here that softer falls

Than petals from blown roses on the grass,

Or night-dews on still waters between walls

Of shadowy granite, in a gleaming pass;

Music that gentlier on the spirit lies,

Than tir’d eyelids upon tir’d eyes;

Music that brings sweet sleep down from the blissful skies.

Here are cool mosses deep,

And thro’ the moss the ivies creep,

And in the stream the long-leaved flowers weep,

And from the craggy ledge the poppy hangs in sleep.II

Why are we weigh’d upon with heaviness,

And utterly consumed with sharp distress,

While all things else have rest from weariness?

All things have rest: why should we toil alone,

We only toil, who are the first of things,

And make perpetual moan,

Still from one sorrow to another thrown:

Nor ever fold our wings,

And cease from wanderings,

Nor steep our brows in slumber’s holy balm;

Nor harken what the inner spirit sings,

“There is no joy but calm!”

Why should we only toil, the roof and crown of things?III

Lo! in the middle of the wood,

The folded leaf is woo’d from out the bud

With winds upon the branch, and there

Grows green and broad, and takes no care,

Sun-steep’d at noon, and in the moon

Nightly dew-fed; and turning yellow

Falls, and floats adown the air.

Lo! sweeten’d with the summer light,

The full-juiced apple, waxing over-mellow,

Drops in a silent autumn night.

All its allotted length of days

The flower ripens in its place,

Ripens and fades, and falls, and hath no toil,

Fast-rooted in the fruitful soil.IV

Hateful is the dark-blue sky,

Vaulted o’er the dark-blue sea.

Death is the end of life; ah, why

Should life all labour be?

Let us alone. Time driveth onward fast,

And in a little while our lips are dumb.

Let us alone. What is it that will last?

All things are taken from us, and become

Portions and parcels of the dreadful past.

Let us alone. What pleasure can we have

To war with evil? Is there any peace

In ever climbing up the climbing wave?

All things have rest, and ripen toward the grave

In silence; ripen, fall and cease:

Give us long rest or death, dark death, or dreamful ease.V

How sweet it were, hearing the downward stream,

With half-shut eyes ever to seem

Falling asleep in a half-dream

To dream and dream, like yonder amber light,

Which will not leave the myrrh-bush on the height;

To hear each other’s whisper’d speech;

Eating the Lotos day by day,

To watch the crisping ripples on the beach,

And tender curving lines of creamy spray;

To lend our hearts and spirits wholly

To the influence of mild-minded melancholy;

To muse and brood and live again in memory,

With those old faces of our infancy

Heap’d over with a mound of grass,

Two handfuls of white dust, shut in an urn of brass!VI

Dear is the memory of our wedded lives,

And dear the last embraces of our wives

And their warm tears: but all hath suffer’d change:

For surely now our household hearths are cold,

Our sons inherit us: our looks are strange:

And we should come like ghosts to trouble joy.

Or else the island princes over-bold

Have eat our substance, and the minstrel sings

Before them of the ten years’ war in Troy,

And our great deeds, as half-forgotten things.

Is there confusion in the little isle?

Let what is broken so remain.

The Gods are hard to reconcile:

‘Tis hard to settle order once again.

There is confusion worse than death,

Trouble on trouble, pain on pain,

Long labour unto aged breath,

Sore task to hearts worn out by many wars

And eyes grown dim with gazing on the pilot-stars.VII

But, propt on beds of amaranth and moly,

How sweet (while warm airs lull us, blowing lowly)

With half-dropt eyelid still,

Beneath a heaven dark and holy,

To watch the long bright river drawing slowly

His waters from the purple hill–

To hear the dewy echoes calling

From cave to cave thro’ the thick-twined vine–

To watch the emerald-colour’d water falling

Thro’ many a wov’n acanthus-wreath divine!

Only to hear and see the far-off sparkling brine,

Only to hear were sweet, stretch’d out beneath the pine.VIII

The Lotos blooms below the barren peak:

The Lotos blows by every winding creek:

All day the wind breathes low with mellower tone:

Thro’ every hollow cave and alley lone

Round and round the spicy downs the yellow Lotos-dust is blown.

We have had enough of action, and of motion we,

Roll’d to starboard, roll’d to larboard, when the surge was seething free,

Where the wallowing monster spouted his foam-fountains in the sea.

Let us swear an oath, and keep it with an equal mind,

In the hollow Lotos-land to live and lie reclined

On the hills like Gods together, careless of mankind.

For they lie beside their nectar, and the bolts are hurl’d

Far below them in the valleys, and the clouds are lightly curl’d

Round their golden houses, girdled with the gleaming world:

Where they smile in secret, looking over wasted lands,

Blight and famine, plague and earthquake, roaring deeps and fiery sands,

Clanging fights, and flaming towns, and sinking ships, and praying hands.

But they smile, they find a music centred in a doleful song

Steaming up, a lamentation and an ancient tale of wrong,

Like a tale of little meaning tho’ the words are strong;

Chanted from an ill-used race of men that cleave the soil,

Sow the seed, and reap the harvest with enduring toil,

Storing yearly little dues of wheat, and wine and oil;

Till they perish and they suffer–some, ’tis whisper’d–down in hell

Suffer endless anguish, others in Elysian valleys dwell,

Resting weary limbs at last on beds of asphodel.

Surely, surely, slumber is more sweet than toil, the shore

Than labour in the deep mid-ocean, wind and wave and oar;

O, rest ye, brother mariners, we will not wander more.February 6, 2011 at 8:10 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #774502Praxiteles

ParticipantBishop Colm O’Reilly announces design team for the restoration of St Mel’s Cathedral, Longford

PRESS RELEASE

6 February 2011

Bishop O’Reilly announces design team for the restoration of St Mel’s Cathedral, Longford

If Christmas 2009 was one of the most painful days of my life as bishop, this is truly a hope-filled and joyful one – Bishop Colm O’Reilly

Today, the feast day of St Mel, the patron saint of the Diocese of Ardagh and Clonmacnois and the Cathedral in Longford, the media launch of the announcement of the design team for the restoration of St Mel’s Cathedral took place in Bishop’s House, Longford. Please see below the addresses by Bishop Colm O’Reilly and Dr Richard Hurley, as well as a letter of support regarding a personal gift of a small stained glass window, Consecration of St Mel as Bishop, from President Mary and Martin McAleese given on St Stephen’s Day, 2009, the day after the fire in the Cathedral started.Key Points

Bishop Colm O’Reilly

•In St Mel’s Cathedral we celebrated a joyful Midnight Mass; dawn revealed a Cathedral ruined by fire. The contrast between the happiness of the Mass at night with the heart-break of Christmas Mass could not have been greater.

•If Christmas 2009 was one of the most painful days of my life as Bishop, this is truly a hope-filled and joyful one.

•It is my hope that this immense challenge that we face will offer us an important opportunity for renewal, not only renewal of a destroyed Cathedral but renewal of a sense of community and creation of an understanding of the purpose that a cathedral fulfils.

•It is in faith that all of us must set out on the journey towards restoration of St Mel’s Cathedral knowing that we will not walk alone, for God is with us.

Dr Richard Hurley

•St Mel’s will rise again and live again as the centre of Catholic life in the Diocese of Ardagh and Clonmacnoise.

•Sacred buildings are a faithful record of the mindset of the times in which they are built. Hence the changes from age to age reflecting man’s relationship with God and the universe. Church buildings shape and influence our religious beliefs.

•While restoring the building is of the utmost importance, every step is being taken to reinstate the heritage of the building, it is ultimately an effective and forward looking liturgical environment which must be the primary consideration. If this can be achieved the Cathedral will live again.

•Part of our task in re-building St Mel’s is to make it a religious space of powerful resonance, respecting the past, living in the present and pointing towards the future. Our committed aim is to restore the Cathedral to its former architectural beauty, with a complementary contemporary liturgical intervention reflecting pastoral aspirations, supported by the arts which will make St Mel’s a worthy flagship of the Diocese of Ardagh and Clonmacnoise and beyond.

Address by Bishop Colm O’ReillyPsalm 29 contains the following beautiful line: “Tears come with the night but joy comes with the dawn”. The psalm does not mean literally that all sadness comes upon us at night time and all happiness with the coming of a new day. In biblical language darkness is disaster, light is deliverance. For the people of Longford at Christmas 2009 it was quite the opposite. In St Mel’s Cathedral we celebrated a joyful Midnight Mass; dawn revealed a Cathedral ruined by fire. The contrast between the happiness of the Mass at Night with the heart-break of Christmas Mass could not have been greater.

Today I believe we are taking an important step towards a new day when we will be able to reverse the disaster of Christmas 2009. The signing of contracts by design team and client for the restoration of our Cathedral marks a new dawn for us. If Christmas 2009 was one of the most painful days of my life as Bishop, this is truly a hope-filled and joyful one.

We have engaged two prestigious architectural firms which have formed an Alliance to plan and guide the restoration of our historic Cathedral. I am extremely pleased to have present at this Press Conference Dr Richard Hurley, our lead Design Architect and Mr Colm Redmond, architect from Fitzgerald, Kavanagh & Partners. We are convinced that these two men and their respective firms which have formed an Alliance can deliver a restored Cathedral which will not just be faithful to its original architectural splendour but also a place of worship which will be inspirational for a new time in the life of the Church in Ireland.

Up to this point the plans for restoration of the cathedral have been handled by Mr Niall Meagher of Interactive Project Managers. This firm was chosen after a very careful search among those with the needed expertise for this key role. They in turn have led the process of identification of the entire design team. I welcome the Director of Interactive Project Managers, Ms Joan O’Connor, who, like Mr Meagher, is an architect.

Our design team can be assured of the full support of the hard working St Mel’s Cathedral Project Committee chaired by Mr Seamus Butler. This committee which has been meeting every second week for many months is attended by a representative of our insurers, Allianz, Mr Gerry O’Toole and the Managing Director of OSG, the Loss Assessors, Mr Danny O’Donohoe.

In the current year, 2011, there is an immense task to be undertaken by the design team. I am convinced that few people in the general population fully appreciate what is involved in planning work. It is easy to see the product of a day’s labour by, for instance, a bricklayer. It is not so in the case of days spent reaching a decision about how best to create a design for a church sanctuary. However, everything about how well the work of restoration is done will depend on how the design team completes the first phase of the work.

It is necessary at the present juncture in our journey towards restoration to invite a high degree of interest in the design work to be undertaken, by all parishioners of Longford and all in the Diocese as well. It will shortly emerge, I can promise, that the design team will engage with the public about the big questions that we need to explore. At an early stage ideas about restoration will be put forward for discussion. It is my hope that this immense challenge that we face will offer us an important opportunity for renewal, not only renewal of a destroyed Cathedral but renewal of a sense of community and creation of an understanding of the purpose that a cathedral fulfils.

At this significant moment it is impossible not to think of the Founder of St Mel’s Cathedral, Bishop William O’Higgins. He laid the foundation stone, taken from the ruins of the old medieval cathedral at Ardagh, in 1840. That day, the 19th of May, was a great occasion in Longford with an estimated attendance of 20,000 people present. No one was to know on that joy-filled day that in seven years time all work would have ceased. In a country decimated by the Great Famine it had begun to look like a ruin, abandoned and overgrown by weeds. However, six years later it would be opened for worship and so it would remain until 2009.

I remember today that Bishop O’Higgins set out with confidence and, while he did not live to see his dream come true, another man was there to complete the work. Many times in history those who lay foundations never see the last phases of the work completed. We cannot predict with anything like certainty when the work we are undertaking will be completed. It is in faith that all of us must set out on the journey towards restoration of St Mel’s Cathedral knowing that we will not walk alone, for God is with us.

+Colm O’Reilly

Address by Dr Richard Hurley

Christmas Day 2009 is a day never to the forgotten in the history of St Mel’s. A tragedy beyond words. That day in the Temperance Hall Bishop Colm O’Reilly promised I quote “together we will rebuild our beloved St. Mel’s Cathedral”. Courageous words in a cataclysmic situation. It may be some consolation to remember and reflect upon the many similar occurrence to Christian places of worship down through the ages and how they rose from the ashes. The most famous example is of the great and majestic Cathedral of Chartres destroyed many times by fire, the last one on the night of 10 June 1194, rebuilt again and consecrated on 24 October 1260, eventually to become one of the glories of Christendom. So it is with the same ardour and belief that St Mel’s will rise again and live again as the centre of Catholic life in the Diocese of Ardagh and Clonmacnoise. The first fruits of Catholic Emancipation, the great ashlar stone Cathedral of St Mel became synonymous with Longford and far flung surrounding counties.

Sacred buildings are a faithful record of the mindset of the times in which they are built. Hence the changes from age to age reflecting man’s relationship with God and the universe. Church buildings shape and influence our religious beliefs. Three types of power influence our perception: divine power, personal power and very importantly the social power between the laity and clergy. Church buildings are gold mines of information on Catholic worship. St Mel’s is no exception. Modern commentators feel it can be best read as an act of faith. It is a classical building in a rural setting. The Madeleine in Paris, The Pantheon and the great Basilicas of Rome inspired Bishop O’Higgins when he became Bishop of Ardagh in 1829. It took fifty three years to bring his dream to completion.

There is no disagreement relating to the beauty of the interior. Unanimity prevails. To quote Christine Casey and Alister Rowan for instance “Keane’s interior is one of the most beautifully conceived classical spaces in Irish Architecture”. Their conclusion “What is beyond doubt is the success of his solution matched with craftsmanship of great quality.” All that, and the priceless artifacts were lost in a few hours on Christmas morning December 2009. Our task is to recreate all that and more, to bring it back to life.

While restoring the building is of the utmost importance, every step is being taken to reinstate the heritage of the building, it is ultimately an effective and forward looking liturgical environment which must be the primary consideration. If this can be achieved the Cathedral will live again. This means the norm for designing liturgical space is the assembly and its liturgies. This is a theology shaped by physical spaces and by what happens in them, creating the environment in which the Cathedral liturgies send out their message of mystery and redemption. More space is required around each of the polarities supporting the celebrations, none more-so than the space surrounding the altar, the centre at the heart of the Eucharist celebration. So, part of our task in re-building St Mel’s is to make it a religious space of powerful resonance, respecting the past, living in the present and pointing towards the future. Our committed aim is to restore the Cathedral to its former architectural beauty, with a complementary contemporary liturgical intervention reflecting pastoral aspirations, supported by the arts which will make St Mel’s a worthy flagship of the Diocese of Ardagh and Clonmacnoise and beyond. This requires more of the heart, and less of the head. The entire team of St Mel’s of which I am honoured to be lead architect, are dedicated towards achieving this objective.

Dr Richard Hurley Arch (6 February 2011)

Letter from President Mary McAleese and her husband Martin to Bishop Colm O’Reilly:

Uachtarán Na hÉireann

President of Ireland

The Right Rev Colm O’Reilly DD

Bishop of Ardagh & Clonmacnois

St Michael’s Cathedral

Longford

6 September 2010

Dear Bishop Colm,

I would like to thank you for your letter and your very kind words which both Martin and I very much appreciate.

We bought the piece, ‘Consecration of St Mel as Bishop’ in an antique shop in the Powerscourt Townhouse Centre, Dublin in 1988. We made it the centre piece in the main window of our home ‘Kairos’ in Rostrevor until we sold the house a couple of years ago. Since then we had been keeping it stored away in our home in Roscommon where we were looking for a suitable place for it. When we heard about the fire at the Cathedral we knew that was the place.

We are delighted to hear that the restoration process of St Mel’s is well underway. Martin and I wish you continued success on that front and look forward to the day when St Mel’s is fully restored.

With warmest good wishes

Yours sincerely

Mary McAleese

President of Ireland

Notes to Editors:

•Bishop Colm O’Reilly was ordained priest on 19 June 1960 and ordained bishop of Ardagh and Clonmacnois on 10 April 1983. the Diocese of Ardah and Clonmacnois has a Catholic population of 71,806. There are a total of 41 parishes in the diocese. The patron saint of the Diocese is St Mel, whose feast day is 7 February. The Diocese of Ardagh and Clonmacnois includes Co Longford, the greater part of Co Leitrim and parts of Counties Cavan, Offaly, Roscommon, Sligo and Westmeath.

•Dr Richard Hurley has wide experience of church architecture, having overseen a portfolio of over 150 church projects in Ireland, Britain, Africa and Australia, includinig St Patrick’s College, Maynooth; St Stephen’s Cathedral, Brisbane, Australia; and Honan Chapel, University College Cork.

Further information:

Martin Long, Director of Communications 00353 (0) 86 172 7678

Brenda Drumm, Communications Officer 00353 (0) 87 310 4444January 28, 2011 at 10:40 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #774500Praxiteles

ParticipantQuite remarkably, J.B. Bullen in his “The Byzantine Revival in Europe and America” devotes litlle or no space to Russia, which is very much the living heir to the Byzantine tradition, and none at all to Vrubel.

January 27, 2011 at 11:34 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #774499Praxiteles

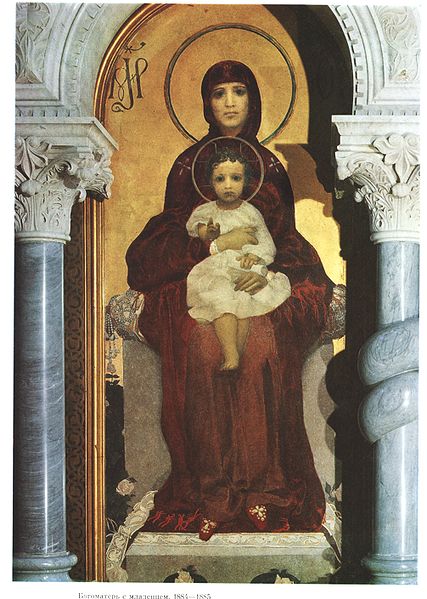

ParticipantVrubel:

Pentecost or the Descent of the Holy Spirit in St. Cyril’s, Kiev

The Theotokos

January 27, 2011 at 11:16 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #774498Praxiteles

ParticipantA note on the Russian neo-Byzantine painter Mikhail Aleksandrovich Vrubel :

Moses

The Madonna and Christ Child, St Cyril’s, Kiev

The interior of the church of St Cyril. KievMikhail Aleksandrovich Vrubel (Russian: Михаи́л Алекса́ндрович Вру́бель; March 17, 1856 – April 14, 1910, all n.s.) is usually regarded amongst the greatest Russian painters of the Symbolist movement. In reality, he deliberately stood aloof from contemporary art trends, so that the origin of his unusual manner should be sought in the Late Byzantine and Early Renaissance painting.

Vrubel was born in Omsk, Russia, into a military lawyer’s family. His mother died when he was three years old. And though he graduated from the Faculty of Law at St Petersburg University in 1880, his father had recognized his talent for art and had made sure to provide, through numerous tutors, what proved to be a sporadic education in the subject. The next year he entered the Imperial Academy of Arts, where he studied under direction of Pavel Chistyakov. Even in his earliest works, he exhibited striking talent for drawing and a highly idiosyncratic outlook. Although he still relished academic monumentality, he would later develop a penchant for fragmentary composition and an “unfinished touch”.

In 1884, he was summoned to replace the lost 12th-century murals and mosaics in the St. Cyril’s Church of Kiev with the new ones. In order to execute this commission, he went to Venice to study the medieval Christian art. It was here that, in the words of an art historian, “his palette acquired new strong saturated tones resembling the iridescent play of precious stones”. Most of his works painted in Venice have been lost, because the artist was more interested in creative process than in promoting his artwork.

In 1886, he returned to Kiev, where he submitted some monumental designs to the newly-built St Volodymir Cathedral. The jury, however, failed to appreciate the striking novelty of his works, and they were rejected. At that period, he executed some delightful illustrations for Hamlet and Anna Karenina which had little in common with his later dark meditations on the Demon and Prophet themes.

In 1905 he created the mosaics on the hotel “Metropol” in Moscow, the centre piece of the facade overlooking Teatralnaya Ploschad is taken by the mosaic panel, ‘Princess Gryoza’ (Princess of Dream).

While in Kiev, Vrubel started painting sketches and watercolours illustrating the Demon, a long Romantic poem by Mikhail Lermontov. The poem described the carnal passion of “an eternal nihilistic spirit” to a Georgian girl Tamara. At that period Vrubel developed a keen interest in Oriental arts, and particularly Persian carpets, and even attempted to imitate their texture in his paintings.

In 1890, Vrubel moved to Moscow where he could best follow the burgeoning innovations and trends in art. Like other artists associated with the Art Nouveau, he excelled not only in painting but also in applied arts, such as ceramics, majolics, and stained glass. He also produced architectural masks, stage sets, and costumes.

It is the large painting of Seated Demon (1890) that brought notoriety to Vrubel. Most conservative critics accused him of “wild ugliness”, whereas the art patron Savva Mamontov praised the Demon series as “fascinating symphonies of a genius” and commissioned Vrubel to paint decorations for his private opera and mansions of his friends. Unfortunately the Demon, like other Vrubel’s works, doesn’t look as it did when it was painted, as the artist added bronze powder to his oils in order to achieve particularly luminous, glistening effects.

In 1896, he fell in love with the famous opera singer Nadezhda Zabela. Half a year later they married and settled in Moscow, where Zabela was invited by Mamontov to perform in his private opera theatre. While in Moscow, Vrubel designed stage sets and costumes for his wife, who sang the parts of the Snow Maiden, the Swan Princess, and Princess Volkhova in Rimsky-Korsakov’s operas. Falling under the spell of Russian fairy tales, he executed some of his most acclaimed pieces, including Pan (1899), The Swan Princess (1900), and Lilacs (1900).

In 1901, Vrubel returned to the demonic themes in the large canvas Demon Downcast. In order to astound the public with underlying spiritual message, he repeatedly repainted the demon’s ominous face, even after the painting had been exhibited to the overwhelmed audience. At the end he had a severe nervous breakdown and was hospitalized in a mental clinic. Vrubel’s mental illness was brought on or complicated by tertiary syphilis.[1] While there, he painted a mystical Pearl Oyster (1904) and striking variations on the themes of Pushkin’s poem The Prophet. In 1906, overpowered by mental disease and approaching blindness, he gave up painting.

January 26, 2011 at 9:14 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #774497Praxiteles

ParticipantFrom the Journal of Sacred Architecture:

Signorelli and Fra Angelico at Orvieto: Liturgy, Poetry, and a Vision of the End-timeby Sara Nair James

2003 Ashgate Publishing CompanyPainting the End of Time

by Michael Morris, O.P.Few scenes are more compelling in Renaissance art than depictions of the Apocalypse and Last Judgment. Certainly Michelangelo’s awe-inspiring and much-photographed Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel has jolted many a sinner to embrace repentance. But before Michelangelo, two artists embarked upon a program depicting the End of Time for the Cathedral of Orvieto. Their contribution, while less known, stands out as a masterpiece of theological painting with visual references not only to scripture, but to literature and liturgy as well. The numerous intellectual influences that helped formulate a work of art during the Renaissance will surprise those readers who have been too long conditioned by the singular and trifling ephemeralities that drive the art world today. Here, the author Sara Nair James, has so skillfully uncovered the various sources that inspired the decorations of the Cappella Nuova, one begins to yearn for a return to the days when art was served by such rich cultural complexities and sublime symbolism.

The Dominican painter Fra Angelico commenced the decoration of the Cappella Nuova in 1447. Professor James points out that Orvieto was a city that had benefited from papal patronage and it was also a place where the Dominican Order exercised much influence. Dominican scholarship had come to full flower within the papal court and throughout Italy by the mid-fifteenth century.

It is, therefore, not surprising that Fra Angelico’s decorative program for the cathedral chapel was influenced by the Order’s emphasis on doctrinal issues, with its optimistic view of the material world and the positive nature of mankind, preached here through paint in a clear systematic way, and with many levels of interpretation. When Fra Angelico was commissioned to do the Orvieto frescoes, he had been working at the Vatican and was considered to be the foremost painter of religious narrative in his day. It was presumed that he would alternate between the Vatican and the Orvieto until the work was completed.

As it turned out, Pope Nicholas V would only release Fra Angelico from Rome for a brief three months of one summer. Nevertheless, the friar accomplished much in that short tenure, presenting in the vault of the chapel an image of Christ seated in judgment that was much more attractive and merciful than the grim scourge of the damned that so typified earlier interpretations of the theme. The painter monk and his assistants only finished two sections of the vault, but left many preparatory sketches. The unfinished chapel languished for many years until 1499 when Luca Signorelli, in the twilight of his career, demonstrated that he could complete the program and adhere to its complex iconography while at the same time preserving the integrity of his own well-established genius.

Signorelli completed Angelico’s decorative program for the sections of the vault that surround the seated Christ as Judge. The groupings of the figures reflect the categories found in the Missal of the Mass. They include Apostles, Angels, Patriarchs, Doctors of the Church, Martyrs and Virgins. And the scenes painted on the walls of the chapel that they witness from their celestial perch are filled with all the drama and pathos that we have come to associated with End Time imagery: the Rule of the Antichrist, Doomsday, the Resurrection of the Dead, the Ascent of the Blessed to Heaven, the Damned Led to Hell, the Torture of the Damned, and the Blessed in Paradise. Professor James interprets each and every scene with such exhaustive scholarship that one can join with others in the academic community who have praised this book as the best overall account to date of Orvieto’s magnificent chapel.

Of particular interest to some readers will be Professor James fascinating claim that Signorelli’s advisors, identified in the documents only as “venerable Masters of the Sacred Page (Holy Scripture) of our City” were in fact Dominican theologians operating from their studium in the nearby Church of S. Domenico. Professor James gives ample evidence to support the idea that Signorelli’s entire program in the chapel is based on Dominican spiritual expositions and the writings of Dante (who was educated by Dominicans). The fact that the decoration of the chapel was originally offered to the Dominican painter Fra Angelico a half-century beforehand brings the scholarship, the spirituality, and the historical linkage full circle. The book demonstrates how the culture of a particular religious order gave rise to the iconography of a complex work of art.

If there be any criticism of the book at all, it would have to be in the quality of its illustrations. Lesser books on Signorelli have clearer and more detailed imagery of the artist’s work at Orvieto. Better to buy some cheap picture book on Signorelli, and use it as a side reference for the treasure trove of insights offered in this masterful study of End Time imagery.

Rev. Michael Morris, O.P., is professor of Art History at Berkeley and author of a monthly column on sacred art in Magnificat.

January 24, 2011 at 5:57 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #774496Praxiteles

ParticipantFour Courts Press, Dublin, has announced details of the forthcoming publication of the proceedings of the Fota II International liturgy Conference, held in 2009, on the subject of Benedict XVI and Beauty in Sacred Art and Architecture and sponsored by St. Colman’s Society for Catholic Liturgy. Here are all the details:

Benedict XVI and beauty in sacred art and architecture

D. Vincent Twomey SVD & Janet E. Rutherford, editors

This volume consists of the proceedings of the second Fota International Liturgy Conference, held in 2009. It explores Joseph Ratzinger’s theology of beauty, with reference to the integral role of art and architecture as the context of liturgical worship.Contents:

D. Vincent Twomey, Introduction;George Cardinal Pell, archbishop of Sydney, The aesthetic theory of Joseph Ratzinger;

Joseph Murphy (Vatican Secretariat of State), The face of Christ as criterion for Christian beauty;

Janet E. Rutherford, The ‘Triumph of Orthodoxy’ and the future of western ecclesiastical art;

Daniel Gallagher (Vatican Secretariat of State), The philosophical foundations of liturgical aesthetics;

Alcuin Reid (liturgical scholar), Noble simplicity revisited;

Uwe Michael Lang (Consultor to the Office for the Liturgical Celebrations of the Supreme Pontiff ), Benedict XVI and the theological foundation of church architecture;

Helen Ratner Dietz (ind.), The nuptial meaning of classic church architecture;

Neil J. Roy (U Notre Dame), The galilee chapel: a mediaeval notion comes of age;

Duncan Stroik (U Notre Dame), Benedict XVI and the architecture of beauty;

Ethan Anthony (Cram & Ferguson Architects), New Gothic and Romanesque Catholic architecture in N. America.

D. Vincent Twomey SVD is professor emeritus of moral theology, St Patrick’s College, Maynooth. Janet E. Rutherford is hon. secretary, the Patristic Symposium,

Maynooth.Hardback

224pp; ills. Summer 2011

ISBN:

978-1-84682-309-1

Catalogue Price: €30.00

Web Price: €27.00January 22, 2011 at 9:47 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #774495Praxiteles

Participant@apelles wrote:

St Joseph & Etheldreda Church restored to original look

The interior at St Joseph & Etheldreda

The interior of at St Joseph & Etheldreda is now a work of art in itself

One of the foremost church restorers in the country says he is extremely proud of his latest achievement – the restoration of St Joseph & Etheldreda Church in Rugeley, south Staffordshire.

The Catholic Revival church, built in 1849, had been badly redecorated during its history.

Tony Skidmore, of Fisher Decorations, based in Stafford, works on restoring listed buildings in this country.

Much of the church’s gold-leafing is now back on view.

The tabernacle at St Joseph & Etheldreda

The tabernacle at the church is brilliantly-colouredThe Grade-II listed church, in Lichfield Street in Rugeley, is the work of Charles Hansom, who built it during the time of the Catholic Revival in England, when Catholics in this country were allowed to start worshipping openly again.

Like similar churches in the county, it has a vibrantly-coloured interior.

Tony Skidmore

Sixty-year-old Tony Skidmore, who started with Fisher Decorations in 1972, specialises in historic renovation. As a member of the National Heritage Training Group he also teaches other craftspeople in what he says are “disappearing” skills.

To restore churches such as St Joseph & Etheldreda he also has to employ history research techniques. He uses archives to discover what the original appearances of the buildings might have been.

“Many of our churches have suffered from years and years of unintentional neglect,” he explained.

“Walls that were once magnificent were painted over by people just wanting to keep things clean and tidy.

“People didn’t realise the beauty they were covering up; and when something had been painted over once there was good chance a second coat would be added in years to come, then another and another.”

Former glory

In Rugeley he has restored walls and ceilings as well as a major statue of Mary & Jesus and other religious works of art.

Using special tools and chemicals Tony peels away the layers to reveal small glimpses of what used to be.

“In some of the cases here we had to peel away ten coats of paint before we got to the original design. Once we discover that design we then have to work out how to replicate it on a wall or ceiling, using, whenever possible, the same materials that would have been used all those years ago,” said Tony.

Skills

Gold-leafing is a dying art, but Tony has two men on his team who are experts. It is the same with the application of lead paint, distemper and lime washes – skills that he says are being left behind, but skills however that are essential for perfect restoration work.

“It is all very time-consuming and expensive work. Nowadays people running the churches are very aware of the hidden treasures they are holding but many just can’t find the money needed to bring them back to life.”

Safeguard

Mark Robinson and Tony Skidmore

Mark Robinson and Tony Skidmore admire the workAs historic homes and churches start to cut back on expenditure in the current climate, restoration businesses like Fisher are affected in turn.

Earlier this year, another West Midlands decorating company stepped in to take over Fisher Decorations – though keeping Mr Skidmore at the head of the company, and safeguarding the jobs of his team for the foreseeable future.

The head of D&R Contract Services, based in Aldridge, Mark Robinson, said he was anxious to see a firm like Fisher continue: “More and more places need this type of work doing and there are fewer and fewer people with the skills to carry it out. Tony and his team are leaders in their field.”

Staffordshire Catholic Revival

Other Catholic churches of the period in Staffordshire include St Giles at Cheadle which was built by the movement’s foremost architect, Augustus Pugin. The style was based on the Gothic buildings of the Middle Ages, so was often called the Gothic Revival.

It’s said that the 19th Century Catholic writer, Ethelred Taunton, who was born in Rugeley in 1857, worshipped at St Joseph & Etheldreda.

St Etheldreda, or Alfreda, is an Anglo-Saxon saint, said to be one the daughters of King Cenwulf of Mercia. The kingdom of Mercia stretched across much of middle England including Staffordshire.

Looks like an excellent restoration of an original colour scheme. And the statue mentioned in the article looks very like something produced by Mayer of Munich.

January 21, 2011 at 11:28 am in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #774494Praxiteles

ParticipantFrom to-day’s Irish Times:

ARMINTA WALLACE

A Christmas conflagration in 2009 appeared to have destroyed the magical Harry Clarke stained-glass windows at St Mel’s Cathedral in Longford – until a miracle of restoration got underway

WE ARE, belatedly, beginning to realise just what a treasure trove is contained in the stained-glass windows of churches all over Ireland – especially those which bear the magical signature of Harry Clarke Studios. These are to stained glass what Lalique is to ordinary glass; and when you look closely at one, you’ll never see any piece of glass – never mind the windows of churches – in quite the same way again. The jewel-like colours, the intricate details, the startlingly contemporary feel, the impish sense of humour – with their huge eyes and elaborate outfits, these saints are startlingly reminiscent of the heroes and heroines of computer games and graphic novels.

But sometimes it takes a catastrophe to make us sit up and pay attention. In the early hours of Christmas Day 2009, fire broke out at St Mel’s Cathedral in Longford. By the time the blaze was extinguished, the church was completely destroyed. In Dublin, Ken Ryan of Abbey Stained Glass Studios was horrified by the television images of the devastation. His company had carried out a full restoration of all of the stained glass at St Mel’s in 1997, so he knew what was likely to be lost forever if something wasn’t done, and quickly.

Ryan and one of his colleagues decided to drive to Longford on St Stephen’s Day. “I called ahead to one of the priests and he said: ‘Don’t come.’ I said: ‘Just tell me, are the Harry Clarke windows intact or not?’ And he said: ‘Everything’s destroyed.’”

They drove on through heavy snow, but when they got to Longford the cathedral was cordoned off for forensic investigation. With the aid of long-distance lenses, Ryan was able to get some idea of what had happened to the windows. “One of the Harry Clarke windows had collapsed, pretty well on to the ground, but there were still pieces of it suspended in the window opening,” he says. “That was the right-hand transept gable as you face the altar. It was Christ in Majesty. On the opposite transept was the Blessed Virgin and the Child Jesus. Every other window was completely gone.”

Glass, when it’s created, is fired at extremely high temperatures – 600 degrees or more – in a kiln. Why, then, is fire damage to stained glass so devastating? “The bed of the window is held together by solder joints,” Ryan explains. “And when the solder gets warm in a fire it melts and runs down to the bottom of the window. So there’s nothing to keep it together. Any gentle breeze or vibration will cause the whole lot to come crashing down.