Praxiteles

Forum Replies Created

- AuthorPosts

- December 15, 2005 at 8:41 am in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767593

Praxiteles

ParticipantRe: # 367

In reply to Antho

4. Ballintubber Abbey, Co. Mayo, 1216

The Abbey was built for Cathal O’Connor for the Canons Regular of St. Augustine in 1216. A fire caused a partial rebuilding c. 1270. The abbey was again burned by Cromwell in 1650 leaving the conventual buikldings destroyed and the nave roofless. The vault of the Chancel survived. Restoraltion began in 1846 but work was suspended because of the Famine. Work resumed in 1887 but the nave was not reroofed until 1966. The Chapter House was restored in 1997 and it is hoped to have the ruins of the east wing of the cloister completed by 2016. The altar shown in the chancel may well be the original altar of the abbey. No drastic intrusions have been made and the church is more or less as one would expect to find a 13th. century conventual church. I am afraid that I have been unable to locate an architect for the 1846 or 1886 restorations or indeed for the present restoration. It seems that the indomitable Archbishop John McHale of Tuam began the 19th century restoration and that the Office of Public WOrks is supervising the present restoration. Unfortunately, the Altar which was at the east end of the Chancel has been moved from its position and placed near the west end of the chancel.

Attending Mass in the unroofed nave of Ballintubber in 1865:

The west door and elevation:

December 15, 2005 at 1:41 am in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767592

December 15, 2005 at 1:41 am in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767592Praxiteles

ParticipantRe. # 376

In reply to Anto

3. Holy Trinity Abbey Adare, Co. Limerick, 1226.

The abbey was dissolved in 1537 and reduced to ruins until Edwin third Earl of Dunraven, a noted antiquarian, restored the abbey Church for Catholic worship in 1852. The architect was Philip Hardwick. The restoration was conducted along the lines of neo Gothic revivalist school and remains a rare example in Ireland of the kind of restoration common in France. Harwick lengthened the nave, built the porch, and the Lady Chapel. The Chancel was fitted out with an arrangement sensitive to the medieval Gestalt of the building. Mercifully, most of the fittings survive in tact. In 1884 Windham Thomas fourth earl of Dunraven installed an interesting gilt bronze screen to searate the Lady Chapel from the nave. The esat window is by Willement. George Alfred conducted a restoration of the building 1977-1980. Following the mode set by Killarney, the plaster was stripped from the walls to leave the buiding bare and lacking its original aspect. It still retains much of the 19the century tile work. Some of the recent artistic additions are at best dubious.

December 14, 2005 at 10:18 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767591

December 14, 2005 at 10:18 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767591Praxiteles

ParticipantRe. # 376

In reply to Anto.

2. Holy Cross Abbey 1180. This is certainly a very fine example of Irish Cistercian architecture and, typical for the order, situated close to a river. This is a true restoration in that the abbey church had been abandoned for over two hundred years. It must be said that the technical aspects of the restoration were carried out to a very high standard and are worthy of praise. The architect for this entire process is Percy le Clerc -to whom great credit must be given for the work done for there was no eperience or other example of an undertaking of this kind in Ireland when he started in 1975. What is rather amazing is that the cloister -at least up to very recently- remains unfinished and gives the impression that the original enthusiasm for the project has dried up. It would be worth completing the job to the same high standards. As at Duiske, the wood work was done to medieval standard and adapted practice. It is authentic and genuine and certainly has none of the faux air about it that is so conspicuous in the work of Richard Hurely and others. I am not sure about the gradiant of the floor. My recollection is that the gradiant increases as one goes towards the west door, thereby leaving the chancel and altar in a depression. My recollection of French medieval churches would have the gradiant reversed, leaving the chancel and the altar on a higer level with the nave of the church. There is a symbolic reason for this: namely, the ascent to Calvary and its association with the sacrifice of the Mass. The liturgical lay out of the Abbey church is, however, another question and a sad one. Again, something has been intruded into a magnificent true medieval setting never intended to take it and which brutally runs rough shod over the entire logic of the medieval building and the reasoning behind its spacial disposition. The main problem, is of course, the cataclasmic abandonment of the Chancel, the “sacred” space of the buiding in which the “actio sacra” takes place. Placing the altar at the crossing effectively renders the most important element of the original composition of space utterly redundant. Michael Bigg’s limestone altar is a monolithic embarrassment and should never have been allowed into such a beautiful and delicate space as Holy Cross Abbey. The same is true of the dreadful lectern and seat (ridiculously placed at a small remove from the magnificent original sedilia) . The liturgical arrangement, as it stands, also has a functional knock on effect on the redundant chancel where we can see the beautiful sedilia (arranged in accordance with the usage of the Roman Rite) shamlessly abused by a clutter of surplus benches and chairs. Even more ironic is the fate of the piscina next to the sedilia. Having survived the ravages of two centuries of war and persecution, it has had what looks like an organ planked in front of it. Would it not have been better, perhaps, had Ireton ripped it out in the same brutal fashion as he had his horsemen drag the high altar out of St. Mary’s Cathedral in Limerick? Who knows. However, one thing is consoling – the late twentieth century dross currently defacing the interior of Holy Cross Abbey can (and I suspect will) eventually be dragged out and dumped. I am not altogether convinced either by the modern shrine containing the relic of the true Cross which is supposed to be the raison d’etre of the Abbey.

December 14, 2005 at 8:04 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767590

December 14, 2005 at 8:04 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767590Praxiteles

Participantre 376:

In reply to Anto:

1. Graiguenamanagh seem to me rather disastrous. From what I can see the altar has been placed on a landing pad under the crossing. Its circular base takes no notice of the rectangular lines of the building, nor indeed of the rather harsh limestone block that serves as an altar.

Graiguenamanagh is a Cistercian monastic church. It would originally have had a monastic choir in antiphonal arrangement (a true one this time) in the space immediately in front of the altar area. Both areas would have been closed off by a screen. Clearly, the present arrangement takes no account of this historical spacial arrangement and consequently, like the Ringkirche in Wiesbaden and many of the so-called re-ordered cchurches and Cathedrals of Ireland, suffers the imposition on it of something it was never intened to contain.

The 1974 restoration was carried out by Percy leClerc. The roof of Irish oak is certainly praiseworthy and authentic. I am not sure that lifting the plaster from the walls can be described as a “restoration”. It is much more likely that they had plastering which was either white washed or frescoed. The removal of the plaster in 1974 smacks of the horrible fashion set by the sack and pillage of Killarney Cathedral. I think that we can take it that if A.W. N. Pugin believed that the Salisbury interior should inspire Killarney, then it should have been white washed and stencilled.

We are told that the new altar was raised on four steps. This is a solecism as principal Altars always had three steps representing the ascent to Calvery or indeed the Old Testament ascent to Jerusalem which we find in the Hallel psalms. Mr. le Clerc offers no explaination for his choice of four (an even number which tended to be avoided). Placing the Altar outside of the East end of the church is of course at complete variance with the whole design of the church and especially insensitive to its line. Placing the Altar in the East end and facing East both have theological significane and meaning – which is shared with the Jews – and is a direct theological reference to the Temple in Jerusalem which has been re-interpreted by the Gospel to mean Jesus Christ, the place in which, as St. John’s Gospel puts it, worship in spirit and in truth is given. There is no theological significance to exposing one’s sefl to the four winds – or worse. Indeed, I am thinking of doing something on the history of Altars in Christian worship, but I may leave it until after Christmas. As far as I can see, leading re-orders such as R. Hurley and Cathal O’Neill know absolutely nothing about the subject if we are to judge from their efforts. From the photographs of Duiske Abbey, the benches leave much to be desired and are not of the quality of their midevial surrpondings. The central heating radiators along the walls are fairly brutal and I am not sure whether the floors have been covered in carpet. The chair at the altar is a mess and looks more like a commode. The ambo is likewise somewhat out of place.

December 14, 2005 at 4:11 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767589

December 14, 2005 at 4:11 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767589Praxiteles

ParticipantDuiske Abbey, Graiguenamanagh 1207

Holy Cross Abbey,1186

As seen by Bartlett in mid 19th century

December 14, 2005 at 3:54 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767588

December 14, 2005 at 3:54 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767588Praxiteles

ParticipantBallintobber Abbey

The Trinitarian Abbey, Adare c. 1230

December 14, 2005 at 3:24 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767587

December 14, 2005 at 3:24 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767587Praxiteles

ParticipantI am glad that you raised this question, Anto. I shall come back to it as it is useful to indicate different approaches to theinterior dispositions the churches you mention, which more or less have had continuous Catholic worship since their construction. Holy Cross is an example of a modern approach. Greiguenamanagh, which I must confess I have not seen, is a modern make over of 19th century restoration and Holy Trinity in Adare which is (more or less) as restored by Harwich for the third Earl of Dunraven in 1855. Ballintubber Abbey in Co. Mayo is, I think, about the only other example of a church in continuous Catholic worship but I have not seen the inside of it.

Re writing to the people responsible for the enforcement of the planning Act in Co. Cork: do you relly think that it would be worth the serious financial committment represented by a postage stamp wrining to them?

December 14, 2005 at 8:49 am in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767585Praxiteles

ParticipantRe 370:

The dumping of all these benches in the Lady Chapel is an example of the conservation Act gone wrong. They have been moved from where they are supposed to be. They cannot be taken out of the building. The building was not designed to have them anywhere else except where they originally were. So, a dumping ground has to be found within the building. In this case, the Lady Chapel was made the dump. INterestingly, Cathal O’Neill’s drawings for the proposed alterations in Cobh show the Lady Chapel as having benches – an absurdity of which he seems unconcious. It also strikes me that two kneelers and chairs that have appeared in the neighbouring Blessed Thaddeus McCarthy Chapel might have more to do with taking the bare look off of the Lady Chapel in it cluttered condition than with the promotion of an intense piety to Blessed Thaddeus. If memory serves me correctly, the Sacred Heart Chapel has also been used for the dumping of a few more benches, his time parked along the dividing screens. What I would like to know is why the Cork County Manager, the Cobh Town Manager, and the Heritage Officer for the County of Cork have allowed this to happen without the slightest murmur?

The laugh is of course that all this goes on while the City of Cork celebrates, with the seriousness of the unknowing, the 2005 European City of Culture!!! Culture, I ask…..

December 14, 2005 at 2:12 am in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767582Praxiteles

ParticipantI can confirm that present state of baisc maintanance of the Cathedral in Cobh leaves a good deal to be desired. Following a visit there earlier in the year, I was horrified to find it it in such a delapidated state and generally unkempt. The Baptistry in particular is a cause for concern. The large brass cover, which should be on top of the font, has been for quite some time left suspended from a bracket on the wall. It is only a matter of time before it comes loose from the wall. It was also noticeable (and it can be seen in the pictures that have been posted) that a section of the marble dado has been hacked off exposing the underlying layer of slate. It was also depressing to see the very beautiful Lady Chapel reduced to a store room for benches that have been displaced from their original positions because an unintelligent attempt to create an antiphonal seating arrangement in both transepts. It is only a matter of time before the particularly fine Oppenheimer mosic in the floor of the Lady Chapel will be wrecked by the abuse to which it is being subjected. I could continue the list but I doubt that Cork County Council is in the least interested in enforcing the law to ensure that this incredibly complex and culturally sophisticated building is treated with the respect that it deserves. As for the clerical guardians of the building, I am afraid to say that the level of education, to say nothing of culture, among them has reached such a nadir that the building would be in more appreciative hands were Radageisus in charge. Cobh Cathedral, and what has been allowed to happen to it, is yet another example of why Ireland is undeserving of anything more than mud and wattle. Unfortunately, it exhibits, in more than cultural terms, the very worst symptoms of the kind of post colonial social malaise that we have come habitually to associate with the furthest reaches of the Limpopo. Clearly, the lack of maintanance of Cobh Cathedral cannot be unintentional and is many ways similar to treatment meated out to preserved structures until they reach a condition that they must be demolished.

December 13, 2005 at 11:38 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767580Praxiteles

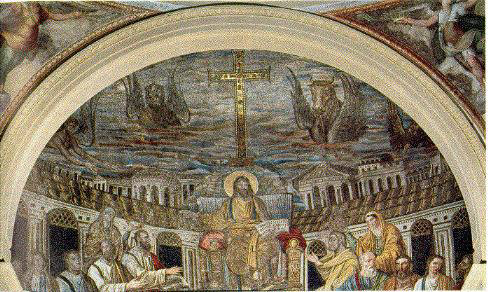

ParticipantThe final stop in tracing the history of the image of Christ in Majecty brings us to the Abbey of Cluny, founded in 909, which for the next 250 years would become a major religious, cultural and political centre in Western Europe. A short history of the movement can be had herehttp://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04073a.htm.

Linked to the reform movement had been the Ottonian dynasty and subsequently the Salian dynast which had established itself in Spire in 1027:http://www.bautz.de/bbkl/k/Konrad_II.shtml. Its political and religious interests lead to the investiture ccrisis and eventually to Canossa: http://www.ulrikejohnson.gmxhome.de/uli/Geschichte/Salier/Salier1.html. It was within both of these two major Western European religious, cultural and political movements that the figure of Christ in Majesty appears on a tympanum for the first time in Western art at the Priory of St. Fortunat in Charlieu in Burgundy

It draws directly on the tradition of iconic depiction that traces its origin to mosaic of 390 in Santa Pudentiana in Rome. While the tympanum of Charlieu represents the full transition of this image from metalwork and illuminated manuscript examples to stonework tympanum around the year 1090, this transition had alrady been underway since about 1020 when the image of Christ in Glory appears on the archatrave of the portal of the abbey of Saint-Genis-des-Fontaines in the Roussillon c. 1020:.

From here, to Charlieu and hence to the Royal Portal at Chartres and from there the image of Christ enthroned in his Majesty arrived to the tympanum of Cobh Cathedral in 1898:

December 13, 2005 at 9:21 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767579Praxiteles

ParticipantA.W. N. Pugin’s St. Giles, Cheadle (1841-1846), built for John Sixteenth Earl of Shrewsbury, and consecreted in 1846,

December 13, 2005 at 9:51 am in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767577Praxiteles

Participantre posting 361

The Ringkirche is a fine building and a good example of the neo Gothic in post-Bismarkian Germany. The arrangement of the interior corresponds and gives expression to Lutheran ideas about the Church, worship and the priesthood and is therefore accomodated to Lutheran needs.

There is a difficulty however. The Church being neo-Gothic depends on types, models, and spacial disposition going back to the middle-ages and beyond. As a neo-Gothic building it refers to ideas about the Church, worship and the priesthood that are much older than those formulated by Martin Luther in the 16 th. century. WHile liturgically the interior of the church is adapted to Lutheran worship, architecturaly it has to be said that the interior suffers from the conjunction of two (at times radically) differing if concepts of Church, worship and priesthood. We have a midevially inspuired shell with a 16th. century inspired interior spacial disposition. the result is that some elements of the building are made redundant. This is most noticeable in the Chancel which is played down to the extent of being almost superfluous.

December 13, 2005 at 1:28 am in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767576Praxiteles

ParticipantThe Golden Antependium of Basel Cathedral

The Golden Antependium was given to the Cathedral of Balsel by the Emperor Henry III to mark its consecration in 1019. It is one of the greates masterpieces of the goldsmith’s art of all times and is a complete synthesis of Ottonian esthetics. The frontal is divided by an arcade, the central arcade ocupied by Christ (standing) with tiny figures of the Emperor Henry II and Empress Cunigunde prostrate at his feet. He is flanked by the archangales Gabriel, Michael and Raphael, and by ST. benedict. The figures are elongated and abstract and suggest forms of splendid transcendence.

December 12, 2005 at 8:52 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767575

December 12, 2005 at 8:52 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767575Praxiteles

ParticipantThe Lombard Kingdom

To return, once again, to the question of the artistic representation of the Majestas Domini, we have followed its development from the mosaic of 390 in Santa Pudentiana in Rome, to the Bizantine Imperial Exarchate in Ravenna and, thence, to the schools of manuscript illumination at Charlemagne’s imperial court at Aachen. In all these cultural contexts, the architpye of Christ enthroned in glory recurrs. The main elements of the Santa Pudentiana mosaic are reproduced in them: Christ seated with imperial poise (though not always sourrounded by the mandorla), the book in his hand, the long hair (though not always bearded), the Cross, the four evangelists and the tetramorphai. This representation of Chirst always emphasises his divinity and the power of the Cross. However, some attention has to be paid to the other great cultural topos of the early middle ages – the Lombard kingdom which had been established in the Po valley and Liguria, as well as in the duchies of Benevento and Spoleto, from the middle of the 6th century when these Longobard tribes came over the eastern Alps from Pannonia and defeated the Bizantine rulers of northern Italy. Their dominance was to continue until their defeat at the hands of Charlemagne. The art of the Lombards was a crucible for various influences: classical Roman, Celt, and Bizantine (evident in the figure of Christ in the Altar of Ratchis as he holds his hand in blessing in the eastern fashion).

http://www.hp.uab.edu/image_archive/ujg/ujgm.html

The Altar of Ratchis c. 740

The altar of Ratchis is the most important monument of the Luitprand renaissance in Cividale. It demonstrates the hight degree of asimilation of Latin civilization by the Lombards. The linear sculpting of the figures is reminiscent of Longobard goldsmithing. The entire altar is the work of a goldsmith done in stone. The composition retains the major elements of the Santa Pudentiana mosaic: the Christ seated in majesty, halo, with the incorporated Cross, the book (this time a rotulus). It also has its own pecularities: Christ wears a stole indicating his priesthood, the hand of God at the top of the manorla, the hand held in the eastern style of blessing, four angels instead of the tetramorphai.

The golden Altar, Sant’Ambrogio in Milan

The Altare d’oro in Sant’Ambrogio was placed over the tomb of St. Ambrose and of Sts. Protasius and Gevasius by the will of Charlemange when Angilbertus was Bishop of Milan (824-859). The treatment of the figures is dynamic and lively. The composition strongly emphasizes the Cross which occupies the central panel of the altar frontal. The Majestas Domini is placed at the centre of the Cross. Instead of blessing, Christ holds the Cross or labrum (reminiscent of ancient Rome and of Moses). The extremities of the Cross contain the tetramorphai representing the Four Evangelists. In each corner is a group of three Apostles.

The victroy of Carlemagne over the Lombards in 774 signalled the end of the Lombard kingdom and the displacement of its artistic accomplishments north of the Alps, eventually to Aachen and the new imperial court.

December 12, 2005 at 3:21 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767573Praxiteles

ParticipantThanks Sangallo for the picture of St. Giles. It is amazing that it has managed to survive – by pure chance, I suspect. Fortunately, in Britain it should be possible to preserve this magnificent building in its integrity thanks to the more competent people who administer the heritage law there. I cannot imagine the Cheadle town council granting planning permission for the wholesale wreckage of this gem. Neither is likely that the law of England would permit an ignoramus to pontificate on plans to dismantle its interior before allowing such to happen. Obviously, we have a little catching up to do in Ireland.

December 12, 2005 at 8:49 am in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767572Praxiteles

ParticipantRe posting 357; In the application for planning permisison submitted to CObh town council by the Trustees of St. Colman’s Cathedral, a “theological” justification for the proposed alterations to the sanctuary was also included. While this item is by no means the theological piece of the year in Ireland (or elsewhere for that matter) I wonder just how different it is from the theological position of the Lutheran authorities who stipulated the conditions for the building of the Ringkirche? I find it extraodrinary that no Catholic bishop in the country, especially the Bishop of Cloyne, seems to have enoough theological training to notice taht the wool is being pulled over their eyes by the kind things built by the “leading” modernist architects. Perhaps the bishops would be better employed attending to what is their own business a little more diligently and leave things concerning the Common Agricultural Policy to those who know best about that. See attached link for what I am talking about:

http://www.foscc.com/downloads/other/Liturgical%20Requirements2.pdf

December 11, 2005 at 9:51 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767571Praxiteles

ParticipantThere is no doubt that A.W. N. Pugin was in contact with his French counterpart A. N. Didron. Indeed, the latter seems to have been influenced in many ways by Pugin and transposed his ideas into the context of the Gothic Revival in France. That Didron was present at the consecration of St. Giles in Cheadle is no surprise. The event probably sets the high water mark of the European Neo Gothic movement with August von Reichensperger, the architect for the completion of Cologne Cathedral, also in attendance. Attached is a letter of Pugin’s to Didron, published in Margaret Belcher’s The Collected Letters of A.W. N. Pugin, OUP, Vol. 2, p. 8.

December 11, 2005 at 1:51 am in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767564Praxiteles

ParticipantFrom 4th/5th century Rome, the artistic type of Christ seated in Majesty, holding a book, surrounded by the Four Evangelists, surmounted by the Cross, spread thoughout Europe. Examples are conserved from the 6th. century on in manuscript miniature, ivory work, and in wrouhgt gold.

The first eample here is from The Book of Kells, folio 32v. Christ, seated in glory, the Cross above his head, at either side a peacock, symbol of eternal life, at either side of his throne, the tetramorphic symbols. The illuminators of the Book of Kells, working probably in Iona, faithfully reproduce the type of Christ’s face to be seen in the moasic of Santa Pudentiana: bearded, with long loose hair (this time blond).

The Gundohinus Gospel of 754

folio 12v

Comparable with Lombard work, especially the altar of Pemmo, Cividale of 731-734In 754, the Carolingian dynasty began. It was the third year of the reign of King Pepin III. Carolingian art was always connected to the court and the royal household. A scribe would be requested to make a copy of a book by a patron. In that same year, at the court of Pepin, a lady, Faustus and a monk, Fuculphus, ordered a scribe named Gundohinus to produce a Gospel Book and oversee its illustration. With this book, the first phase of Carolingian manuscript painting began. His work appears to have been strongly influenced by the art of Lombardy, a part of Northern Italy that had maintained contact with the Byzantine world. However, the work does not appear to reflect a thorough understanding of the classical modeling techniques. Although hatch marks were used by this early Carolingian artist in an attempt to describe the volumetric quality of the human and animal forms, they are not convincing. They indicate that the artist copied classical models, but without conviction. In his hands the repetition of curvilinear marks do little to describe the three-dimensional shape of the form and relieve the flatness of the picture plane. In Christ in Majesty, there are five figures organized in five circles. Christ seated on a throne, flanked by two angels, occupies the center while the four symbols of the Evangelists in four smaller circles surround the image of Christ. The decorative borders of each circle consist of simple schematic foliage or white dots. As we will see, Carolingian painting style develops quickly from here.

Here Christ is clean shaven, long hair, and the Cross has been absorbed into the halo:

The Gosescalc Gospel

f. 3r.

Christ in Glory influenced by the Book of Kells and by an image in Santa Maria in Trastevere in Rome

In the year 781, Pepin’s son Charles (i.e. Charlemagne) met Pope Adrian I in Rome. Upon his return Charles ordered Godescalc, a friend and a Frank, to make a Gospel Book to commemorate his meeting with the Pope. This was the beginning of the true style of Carolingian art. Godescalc modeled his work after Late Antique or Classical sources, as did Gundohinus. However, the illustrations in the Godescalc Gospels are clearly the work of a painter who has mastered the techniques of naturalistic illusionism to the extent that the linear outlines of the folds of fabric convey volume. In addition, shading in light and dark and the use of highlights on the garments and flesh of the Evangelists are quite sophisticated and subtle. The colors are cool and somber. The labeling of the evangelist in the image was a common device in Hiberno-Saxon manuscripts. The rectangular frame here, with simplified vegetation flatly drawn in a rhythmic pattern, is reminiscent of the style of Late Antique manuscript illustrations. The overall effect demonstrates that a great deal has been learned since the Gundohinus illustrations of twenty seven years before. Regrettably, much of this particular style ends with Godescalc, thereby closing the first phase of Carolingian illustration.

The Ada Gospels

folio 85v, St Luke

Texts continued to be produced for some years after the Gospel Book of Godescalc, but without illustrations. However, in time, manuscript illustration reappeared. Sometime close to the year 785, a manuscript called the Ada Gospels was produced. The first part was not illustrated, but the second part, made later, was illustrated.

The Ada Gospels are a fine example of the Carolingian artist’s grasp of Classical style. The architectural elements that are included are executed in a highly confident manner. Where the environment of the evangelist in the Godescalc paintings is ambiguous, the evangelists in the Ada gospels are clearly located in a well constructed architectural setting. They are portrayed seated on a throne decorated with panels imitating architectural elevations with rows of windows, repeating the design of the walls surrounding the evangelists. The scene is framed with a traditional classical device of Corinthian columns topped by an arch. Inside the arch, filling the space above the architecture and the evangelist’s head, is a large representation of the symbol of the evangelist. In the case of St. Matthew (see Hubert, Carolingian Art, bibliography, p. 79), it is an angel whose wing span reaches to the border of the arch on either side. The angel seems to be reading from a scroll spread wide in his outstretched arms. St. Matthew’s head is tilted as if he is listening carefully to the angel’s words. His hand is held poised above the page ready to transcribe the inspired Word. These two features–the monumental architecture and powerful image of the angel–give the image a majestic quality. The feeling one gets from this well-ordered composition, beautifully rendered in peaceful pastels, is a sense of quiet grandeur.

http://content.answers.com/main/content/wp/en/b/bf/AdaGospelsFol85vLuke.jpg

Evangeliary of Metz

Sacramentary of Soisson 800-820

The Lorsch Gospel c. 800

folio 18v

In this example of Christ in majesty, the right hand is raised in blessing with the fingers in the Greek manner of imparting blessings.

http://www.faksimile.ch/cgi-bin/upload/images/LOR_AJ_gr_RGB.jpg

http://www.geocities.com/Athens/Aegean/7023/Lorsch.html?200512

http://www.faksimile.ch/werk01_e.html

Sacramentary of Metz 870

folio 3r

St. Gregory the Greathttp://www.library.nd.edu/medieval_library/facsimiles/litfacs/metz/3r-1L.jpg

For an overview of the Western manuscript tradition see the following link:

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09614b.htm

Below:

1. A manuscript from c. 800

2. The Gundonius Gospel of 754

3. An early ivory (Bodlian, Oxford)December 11, 2005 at 12:46 am in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767563Praxiteles

ParticipantDear Boyler,

See posting # 96 and you can see exactly what happened to Longford Cathedral.

December 10, 2005 at 9:54 pm in reply to: reorganisation and destruction of irish catholic churches #767559Praxiteles

Participant

To return to the subject of the mosaic of Santa Pudenziana with its depiction of Christ seated in glory, surrounded by the tetramorphai, we pointed out in posting # 342 the various elements of the mosaic borrowed from pagan Greek and Roman art to depict Christ in such a way as to attribute divinity to him. Seeing these, the average Roman or indeed Greek pagan of the year 390 would automatically assume from the figure of Christ in the ,mosaic that he was a divine person – since his depiction repeats all of the usual elements of Roman and Greek art to underline the quality of divinity (the halo, the beard, the long loose hair, his session on a type throne reserved to Jupiter). The question is: why the emphasis on Christ’s divinity and the insistence on it? The answer probably lies in the theological culture of the time which was heavily dominated by the Arian heresy, specifically denying the divinity of Chirst, which was condemned at the Council of Nicea in 325. Clearly, the Basilica of Santa Pudenziana in 390 was in the hands of orthodox Catholic worship which may explain the rather pointed script on book held by the Christ figure:Dominus Conservator Ecclesiae Pudentianae (The Lord is the protector of Pudentiana’s Church). The broad outline of the controversy can be seen by following this link:

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01707c.htm

However, while pagan artistic prototypes were used to create a depiction of Christ that would assert his divinity, the scene which is being depicted is taken directly from the last book of the Bible, the Revelation (or Apocalypse) of St. John chapter 4: 1-11. The Text reads:

” 1After this I looked, and behold, a door standing open in heaven! And the first voice, which I had heard speaking to me like a trumpet, said, “Come up here, and I will show you what must take place after this.” 2At once I was in the Spirit, and behold, a throne stood in heaven, with one seated on the throne. 3And he who sat there had the appearance of jasper and carnelian, and around the throne was a rainbow that had the appearance of an emerald. 4Around the throne were twenty-four thrones, and seated on the thrones were twenty-four elders, clothed in white garments, with golden crowns on their heads. 5From the throne came flashes of lightning, and rumblings[a] and peals of thunder, and before the throne were burning seven torches of fire, which are the seven spirits of God, 6and before the throne there was as it were a sea of glass, like crystal.

And around the throne, on each side of the throne, are four living creatures, full of eyes in front and behind: 7the first living creature like a lion, the second living creature like an ox, the third living creature with the face of a man, and the fourth living creature like an eagle in flight. 8And the four living creatures, each of them with six wings, are full of eyes all around and within, and day and night they never cease to say,

“Holy, holy, holy, is the Lord God Almighty,

who was and is and is to come!”9And whenever the living creatures give glory and honor and thanks to him who is seated on the throne, who lives forever and ever, 10the twenty-four elders fall down before him who is seated on the throne and worship him who lives forever and ever. They cast their crowns before the throne, saying,

11′ Worthy are you, our Lord and God,

to receive glory and honor and power,

for you created all things,

and by your will they existed and were created’ “.The text of Revelations is not an isolated text in Biblical literature and must be situated in the tradition of the Jewish apocalyptic liteature of the Old Testament on which it draws heavily. In the case of the heavenly court the borrowing comes specifically from the Prophet Ezekiel chapters 1 and 10 (http://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?book_id=33&chapter=1&version=47 and http://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?book_id=33&chapter=10&version=47) where we find the the four beasts, the ealders and the Deity seated on the throne.

The novum of Revelations, however, is that Christ is placed on the heavenly throne thereby asserting, in Jewish terms, that he is God, thereby making the basic profession of Christian faith, namely, that Jesus is Lord.

The beasts described by Ezekiel reappear in Revelations and surround the throne. At this point, they are not associated, at least explicitly, with the four Evangelists. That association would first be made by Irenaeus of Lyons (died 202) in his Adversus Haereses, Book III, chapter 3, paragraph 8 (http://www.ccel.org/fathers2/ANF-01/anf01-60.htm#P7409_1981656) written c.175-185 A.D.. This text gives us the historical terminus a quo for the artistic tradition of the depiction of Christ to be found in the tympanum of the West door in Cobh Cathedral. It supplies the original historico-cultural context for that depiction, which is the Arian heresy and the measures taken to counter it. It also supplies us with the interpretative key for reading and understanding both the theological and artistic concerns lying behind the artistic type: Christ’s divinity.

- AuthorPosts