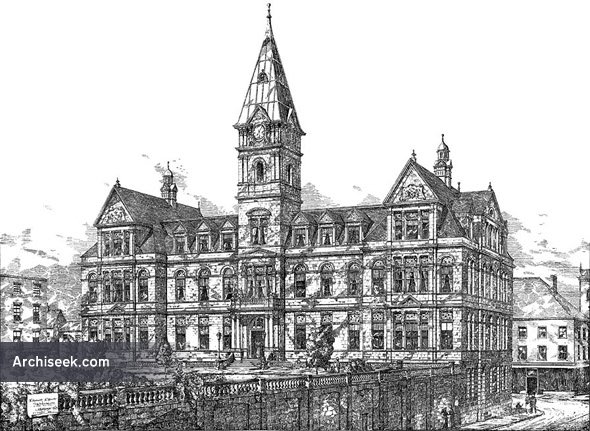

1888 – Halifax City Hall, Nova Scotia, Canada

Perspective View published in The Architect, November 25th 1887. In 1886 Halifax City Council asked for competitive plans for a proposed city hall. Of the architects who submitted plans, the Board of Works recommended to Council that the architect, whose plans were marked “Gladstone”, should receive a first prize of $300. Although the Board of Works recommended Gladstone’s as the best, it believed some modifications and alterations in the internal arrangements should be made. City Council deferred making any decision to allow for due consideration.

Gladstone’s plans did not meet with universal public approval. One writer to the Morning Herald newspaper, who called himself “Critic”, felt that the “south front facing the parade is not half good enough for the fine approach, which in my opinion can not be beaten in America”. He found the entrance on the plan “insignifi cant”. Instead, he recommended that “the doorways should be set off with a fine flight of steps and columns etc., and should be with the clock tower a notable feature of the design”. Besides, the plans made no provision for a town hall where public meetings, balls, concerts and receptions could take place, as usual in England and the United States. City Council had intended to spend $75,000, but this sum Critic considered “too paltry” for so noble a site – let Councillors “take Gladstone in hand and give him new orders to make his plans worthy of the times”. Since taxpayers would have to pay the piper, Critic concluded “we might as well have good music as bad”.

On the day before City Council was to make its decision, Haligonians had their first real view of the plans when The Citizen and Evening Chronicle published front, rear and side views of “The Noble Structure”. The paper also provided an extensive written description and history of the project. On 22 October at a special meeting, and after considerable debate, Halifax City Council adopted Gladstone’s plans. Gladstone proved to be Edward Elliot, a Dartmouth native, who had trained in Boston and returned to Halifax where he operated from a Bedford Row office.

For his entry, Elliot chose the Second Empire style, a style that had had a meteoric rise since its grand use in Napoleon III’s France (1852-1870) for public buildings. Second Empire became immensely popular in the 1870’s and 1880’s and typified the increasingly elaborate and monumental appearance of architecture in this era. In England, it had found much favour and both the War Offi ce and Foreign Office buildings were built in this style. It was equally popular in the United States in the rebuilding after the American Civil War. In Canada, it became the choice of the new Dominion government for numerous public buildings and the provinces followed suit. Two examples with strong architectural resemblances to Elliot’s design were the MacKenzie Building at the Royal Military College, Kingston, constructed 1876-78, and the far more massive, Quebec’s Legislative Assembly Building, begun in 1877 and completed in 1887.

The Second Empire’s most distinguishing stylistic feature was the mansard roof, a double pitched roof with a steep lower slope. Mansard roofs had the practical advantage of giving added space to the attic floor. In his design, Elliot used most aspects of the style, including the mansard roof and a central tower incorporating a clock, with bays jutting out at either end to create a monumental effect. And this may have been its most appealing aspect to both the Board of Works and City Council. They sought a design that would be a visually prominent landmark, do justice to the Grand Parade site, and be a symbol of a progressive and vibrant city.

Elliot’s design underwent a series of modifications. On 5 December 1888, the Acadian Recorder published a design that included a proposed additional storey. It had ornamented fenestration and an imposing tower. Still more changes were made to the fenestration and to the tower and finer facade articulation before Keating and Elliot settled on the final design. They did not, however, include an additional storey. What had begun as a rather austere four-storey building became a structure with a variety of decorative elements designed to reflect more the Second Empire style and in the process enhance its monumental character.

The City Hall building was designated a National Historic Site in 1997 as one of Nova Scotia’s oldest and largest public buildings.